ARISTOTLE

NICOMACHEAN ETHICS Introduction

By Bill Weintraub

Aristotle's most important book on what we would call ethics or morals or goodness is titled the Nicomachean Ethics.

Throughout the book, Aristotle uses the word αρετη to refer to what is often translated as "virtue" or "virtues."

But that translation is misleading.

Indeed, it's so misleading that H. Rackham, the Fellow of Christ's College, Cambridge, who translated the Ethics in 1926, sometimes uses the phrases "excellence or virtue" and "excellences or virtues" -- to refer to the single word αρετη.

Because αρετη does not mean "virtue" in the Judeo-Christian sense.

It means, as we've often heard classicist Werner Jaeger say, "excellence" :

Remember that the Greek for 'good' [agathos] does not merely have the narrow ethical sense we give it, but is the adjective corresponding to the noun areté, and so means 'excellent' in any way. From that point of view ethics is only a special case of the effort made by all things to achieve perfection.

"From that point of view" -- which is the Greek point of view, the Greek Warrior point of view -- "ethics is only a special case of the effort made by all things to achieve perfection."

So :

Agathos "is the adjective corresponding to the noun areté, and so means 'excellent' in any way."

Which means that if it refers to a Man, it means Manfully Excellent -- which is Manly -- which is Willing and Able to Fight.

That's what it means.

It refers to the Excellence of a Man, which is Fighting.

And a Man, to be Excellent, must be Willing and Able to Fight.

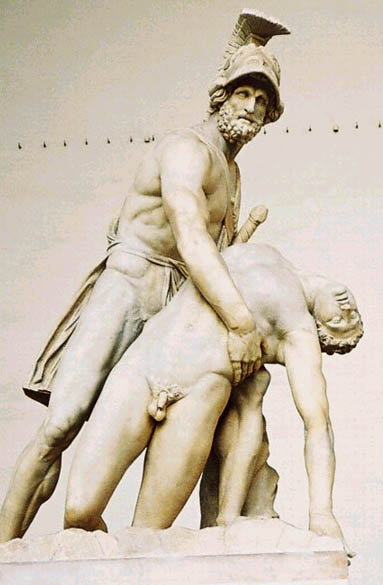

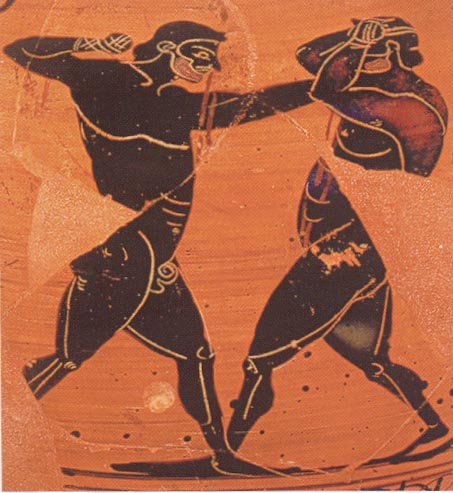

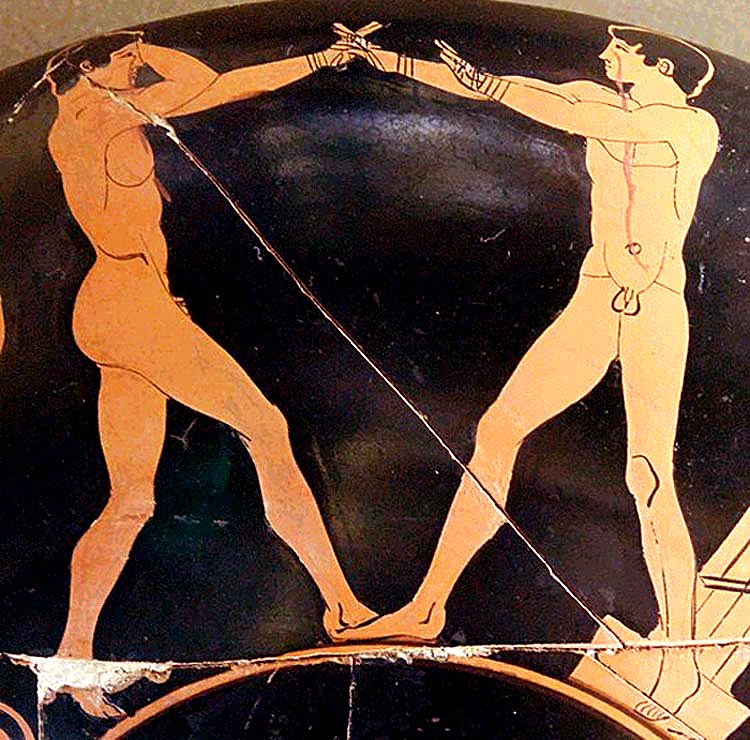

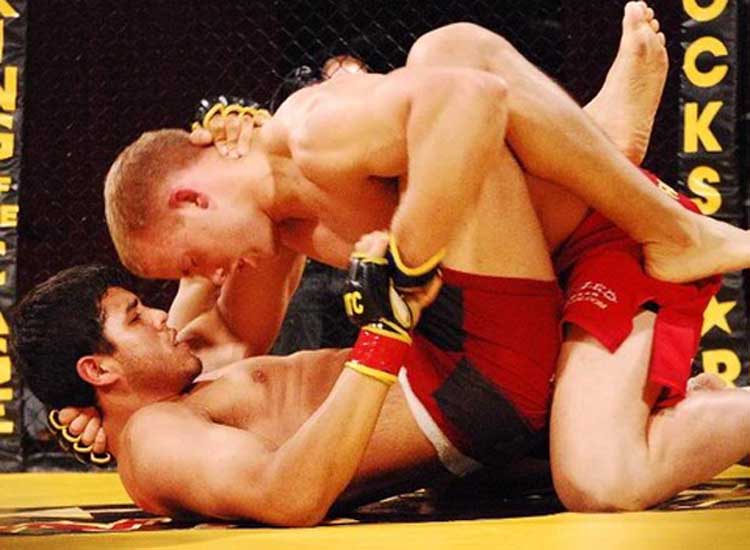

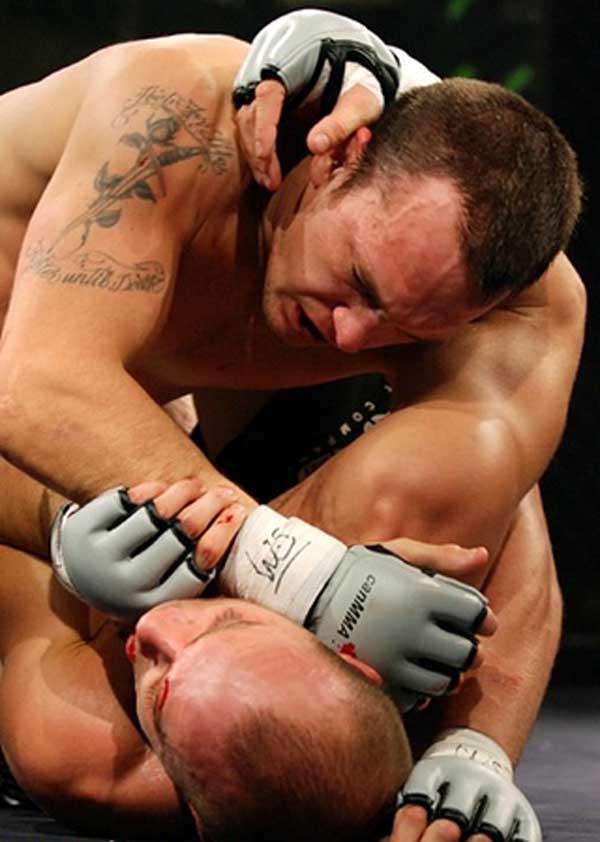

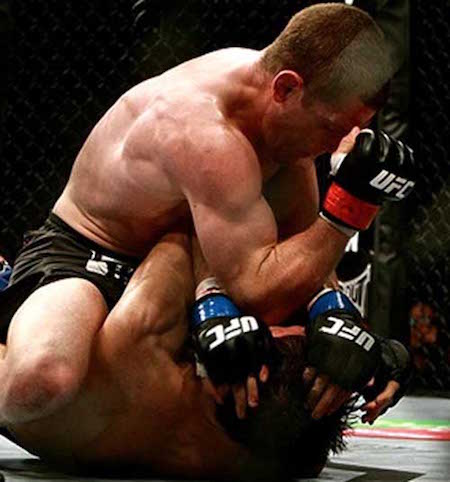

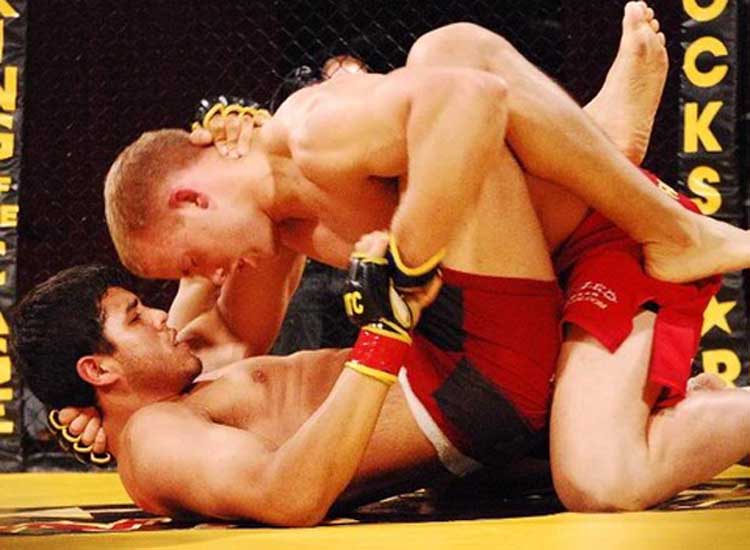

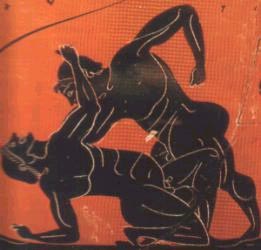

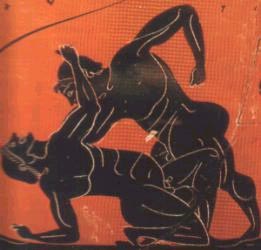

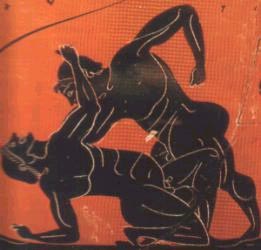

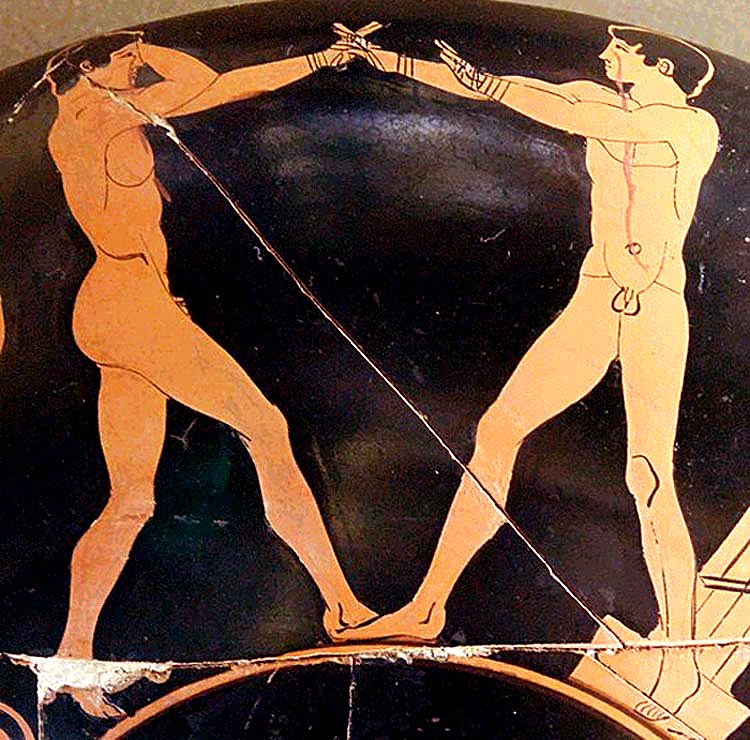

Which means that Warrior Ethics, which is Manly Ethics, Manly Virtue, Manly Wisdom, and above all, Manly Goodness, is epitomized by Two Men, Two Nude Fighting Men, Struggling to Perfect Their Manly Excellence, Their Fighting Manhood, Their Manliness.

Jaeger says so.

He says that what we call "ethics" is, to the Warrior Greeks, only a special case of the effort made by all things -- to achieve perfection.

Perfection being the Excellence which pertains to each existent thing.

So :

The Excellence of an Eye is Seeing -- what we might call Ocular Excellence.

And the Excellence of an Ear is Hearing -- what we might call Aural Excellence.

While the Excellence of a Man is Manliness and its attendant Fighting -- Fighting With and Against Another Man.

Which we call Manly Excellence.

Which is Manliness.

Moreover :

Jaeger speaks of "Men Struggling to Perfect Their Manhood in Victory" -- and that's what Aristotle, whose guide in ethical matters is the Homeric Nobility, that is, the Great Warriors of the Iliad -- that's what Aristotle, per Rackham, is saying : "the aim of a living organism, the final cause of its being, is to realize the potentiality of its nature, to grow into a perfect specimen of its species" :

Translation : The aim of the living organism Homo Sapiens, the final cause of its being, is to develop, through strenuous physical struggle, into the perfect specimen of its species -- the Fighting Man, the Warrior, defined and delineated by his Fighting Manhood, his Victorious Fighting Manhood.

So :

Αγαθος, which is the adjectival form of αρετη, means "excellent" in any way.

And αρετη, when preceded by the term ethical, means ethical excellence.

But that's not the same as ethical virtue in the Christian sense.

Nonetheless, Rackham and other translators do often use the word "virtue," and, I suppose, so must we, so long as we understand that what the Greeks meant by Ethical Virtue is way way way way different, from what our society means by it.

Because to the Greeks, Ethical Virtue is intertwined with Fighting.

The two cannot be separated.

Indeed, the very last paragraph of Rackham's Introduction says,

[Aristotle's] review of the virtues and graces of character that the Greeks admired stands in such striking contrast with Christian Ethics that this section of the work is a document of primary importance for the student of the Pagan world. But it has more than a historic value. Both in its likeness and in its difference it is a touchstone for that modern idea of the gentleman, which supplies or used to supply an important part of the English race with its working religion.

Why does Rackham say "which supplies or used to supply" ?

Because he's writing in 1926, that is to say, after 1915, and it was in 1915, during the First World War, that Men began questioning an ethical system based upon Fighting.

Nevertheless, from the Renaissance forward, "an important part of the English race" -- and really an important part of the Western World -- was educated primarily in the Greek and Roman classics, classic books written by Men such as Homer, Plato, Xenophon, Aristotle, Cicero, Virgil, Horace, and Arrian --

In all of which Fighting is essential, and in which Manliness -- the Willingness and Ability to Fight -- is the chief Excellence or Virtue of a Man.

So :

Αρετη means excellence.

And when referring to a Man, it means Manly Excellence, or Manly Virtue, which is the Willingness and Ability to Fight, and which is Manliness -- ανδρεια.

Manliness, according to Aristotle, is the most important of the Pagan Virtues or Ethics referenced by Rackham above.

It appears at the very top of Aristotle's list, and he gives Manliness a far more extended discussion than any of the other virtues or ethics --

Other than Justice, and that's because to Aristotle, there are many kinds of Justice, all of which must be discussed.

Nonetheless, Manliness appears at the very top of Aristotle's list, and he gives Manliness a far more extended discussion than any of the other virtues or ethics.

That's because Manliness -- the Willingness and Ability to Fight -- deals very directly with pleasure and pain -- and pleasure and pain are central to Aristotle's understanding of what ethics are, and are about.

Aristotle :

"It is for facing what is painful that Men are called Manly."

Though Manliness is concerned with feelings of confidence and fear, it is not concerned with both alike, but more with the things that inspire fear ; for he who is undisturbed in face of these and bears himself as he should towards these is more truly Manly than the man who does so towards the things that inspire confidence. It is for facing what is painful, then, that Men are called Manly. Hence also, then, Manliness involves pain, and is justly [dikaios] praised ; for it is harder to face what is painful [luperos] than to abstain from what is pleasant.

And please take note of this :

Aristotelian WD Ross says,

"The motive of Manliness is the sense of Honour."

The Motive of Manliness -- that which leads the Man to Fight -- is the Sense of Honour.

Honour enables and impels Fighting.

From time immemorial guys have said, I Fought because it would have been dishonourable not to, I Fought because it was the Honourable thing to do, because it was and is Honourable to Fight.

So :

Fighting and Manliness are symbiotic.

Fighting confers Manliness. -- We learn to be Manly by being Manly -- by Fighting -- by standing up to blows face to face.

And Manliness, in turn, enables Fighting.

And in back of all of that is HONOUR.

The Motive of Manliness -- the Motive of Fight -- is the Sense of Honour.

Honour impels Men to Fight.

Honour impels Men to Fight.

Aristotle :

And the Manly Man will endure terrors as principle dictates, for the sake of what is Noble -- Καλον -- for that is the end at which moral virtue aims.

It is the Fighter's willingness to endure the terrors, to endure the pain -- to face the pain and take the pain -- which makes the act Beautiful.

Uniquely Beautiful.

Noble and Beautiful.

Honourable and Beautiful.

Aristotle :

What form of death then is a test of Manliness [andreia]? Presumably that which is the noblest [kallistos]. Now the noblest form of death is death in battle [polemos -- battle, fight, war], for it is encountered in the midst of the greatest and most noble of dangers [megistos kai kallistos kindunos]. And this conclusion is borne out by the principle on which public honours [Tima] are bestowed in republics and under monarchies.

The Manly Man [ho andreios], therefore, in the proper sense of the term, will be he who fearlessly confronts a noble death [kalos thanatos], or some sudden peril that threatens death ; and the perils of polemos -- battle, fight, war -- answer this description most fully.

Aristotle :

And every activity aims at the end [telos -- fulfillment, completion, consummation, result] that corresponds to the disposition of which it is the manifestation. So it is therefore with the activity of the Manly Man [ho andreios] : his Manliness is noble [kalos] ; therefore its consummation is nobility [kalon], for a thing is defined by its consummation ; therefore the Manly Man endures the terrors and dares the deeds that manifest Manliness, for the sake of that which is noble.

~Aristotle, Nikomachean Ethics, 1115a-6, translated by Rackham and myself.

Again, Kalos at its most basic means both Noble and Beautiful.

And it's pain -- the pain of Fight -- and the Fighter's Willingness to Face and Take that Pain -- which confers Nobility and Beauty.

I'll have more to say about this -- below.

For now :

The end at which moral virtue -- ethical excellence -- aims, is Nobility -- Καλον -- Kalon ; and, as we discussed in The Combative Congregation, Kalon is a term of admiration for bodies well made, actions well done.

Καλον -- Moral Nobility -- which is Manliness.

And the action in question is always Fighting :

Bill Weintraub

21 November 2021

Updated :

17 February 2023

So that's a short introduction to Aristotle, and you can see that Aristotle is very much about Manliness and Fighting.

To Aristotle, Manliness is the Supreme Ethical Excellence aka Moral Virtue, and Manliness is conferred by Fighting.

And you can see, too, that Aristotle is also very much about Areté / Areta.

Areté / Areta is the most important word in ancient Greek -- and if you haven't clicked on the definition and read the entire page, you should : Areté / Areta ;

Because Areté / Areta is the most important word in the Greek language ; and, as we discussed at length in Fighting Manhood is the Father and Sum of all the Excellences of Man --

Areté / Areta derives from Ares ;

And Areté / Areta means Manhood ; Fighting Manhood :

And

[Areta itself is] goodness, excellence, of any kind, esp. of manly qualities, manhood, valour, prowess (like Lat. virtus, from vir)

So :

The most important word in the ancient Greek language and in the culture of ancient Greece, which is the foundational culture of the Western World, is Areta ;

and Areta derives from and is rooted in the Warrior God Ares, the God of Battle-Fight-War ;

and Areta means Manhood -- Fighting Manhood.

It doesn't mean vagina, it doesn't mean feminism, it doesn't mean tranny.

It means Manhood -- Fighting Manhood.

And that term itself derives from Man.

Here's more about Aristotle, especially about the importance of training and habit in inculcating Manliness :

To Aristotle, every moral virtue, every ethical excellence, exists as a mean between a vice of excess, and one of defect.

For example, the moral virtue of Generosity.

The vice of excess is prodigality -- the tossing away of one's money.

The vice of defect is meanness -- the refusal to help a friend in need.

Similarly, and regarding the Supreme Moral Virtue and Ethical Excellence of Manliness, the vice of excess is over-confidence or rashness ;

while the vice of defect is UN-manliness, effeminacy, cowardice, which is the unwillingness to face pain, the fear of pain.

Aristotle :

[10] He that exceeds in fear is a coward, for he fears the wrong things, and in the wrong manner, and so on with the rest of the list. He is also deficient in confidence ; but his excessive fear in the face of pain is more apparent.

[11] The coward is therefore a despondent person, being afraid of everything ; but the Manly Man [ho andreios] is just the opposite, for confidence belongs to a sanguine temperament.

[12] The coward, the rash man, and the Manly Man are therefore concerned with the same objects, but are differently disposed towards them : the two former exceed and fall short, the last keeps the mean and the right disposition. The rash, moreover, are impetuous, and though eager before the danger comes they hang back at the critical moment ; whereas the Manly are keen at the time of action but calm beforehand.

[13] As has been said then, Manliness is the observance of the mean in relation to things that inspire confidence or fear, in the circumstances stated ; and it is confident and endures because it is noble [kalos -- noble, honourable] to do so or base [aischros -- shameful, base, dishonourable, ignoble] not to do so.

~Aristot. Nic. Eth. 3.7.11, translated by Rackham and myself.

So :

What Aristotle tells us is that the essence of the defect and vice of UN-manliness, effeminacy, cowardice -- is the coward's "excessive fear in the face of pain."

The essence of the vice of UN-manliness is the fear of pain and the inability to face pain.

"It is for Facing what is Painful that Men are called Manly."

And it's for fearing what is painful and refusing to face that pain -- that males are called, and behave as, UN-manly, effeminate, cowards.

How does a person learn to face pain ?

By facing pain.

Aristotle -- and the other Greeks -- all say so.

How does a young person, a young man, a youth -- learn to stand up to blows face to face ?

By standing up to blows face to face.

Again, the ancients all agree :

Moral Virtue -- all Moral Virtue -- is a question of habit.

Habit which has been carefully and ceaselessly inculcated since childhood.

And which results in what Cicero calls Fortitudo, which is Virtus, which is

Scorn of death and scorn of pain.

As Aristotle explains :

Aristotle :

[II] Virtue [αρετη -- excellence] being, as we have seen, of two kinds, intellectual and moral [διανοητικος kai ηθικοσ], intellectual excellence is for the most part both produced and increased by instruction, and therefore requires experience and time ; whereas moral or ethical excellence is the product of habit (ethos), and has indeed derived its name, with a slight variation of form, from that word. [a]

Footnote:

[a] Prof Rackham : It is probable that εθοσ, 'habit' and ηθοσ, 'character' (whence 'ethical,' moral) are kindred words.

Bill Weintraub : So that ηθικοσ αρετη -- ethical excellence -- is the product of εθοσ -- habit.

[2] And therefore it is clear that none of the moral excellences formed is engendered in us by nature, for no natural property can be altered by habit. For instance, it is the nature of a stone to move downwards, and it cannot be trained to move upwards, even though you should try to train it to do so by throwing it up into the air ten thousand times ; nor can fire be trained to move downwards, nor can anything else that naturally behaves in one way be trained into a habit of behaving in another way.

[3] The virtues [a] therefore are engendered in us neither by nature nor yet in violation of nature ; nature gives us the capacity to receive [b] them, and this capacity is brought to maturity by habit.

Footnotes:

[a] Prof Rackham : αρετη is here as often in this and the following Books employed in the limited sense of 'moral excellence' or 'goodness of character,' i.e. virtue in the ordinary sense of the term.

Bill Weintraub : Put differently, when Prof Rackham uses the English word 'virtue', he means moral virtue and/or ethical excellence ; and the most important and paramount ethical excellence, which comprehends all the others, is Manliness.

[b] Bill Weintraub : Aristotle says that nature gives us the capacity to receive the virtues -- and that capacity is discussed in our List of Warrior Theurgic Words, beginning with the word Form and continuing through Matter, Receptacle, Scission, and Substantiality.

And you must read that section -- that is, from Form through Substantiality -- which isn't long.

Nevertheless, you have to read it because, as Prof Rackham points out in his Introduction, Aristotle "assumes in his reader a knowledge of Plato's writings" -- and you have to have that knowledge in order to understand what Aristotle is saying.

[4] Moreover, the faculties given us by nature are bestowed on us first in a potential form ; we exhibit their actual exercise afterwards. This is clearly so with our senses : we did not acquire the faculty of sight or hearing by repeatedly seeing or repeatedly listening, but the other way about -- because we had the senses we began to use them, we did not get them by using them.

The virtues on the other hand we acquire by first having actually practised them, just as we do the arts. We learn an art or craft by doing the things that we shall have to do when we have learnt it : for instance, men become builders by building houses, harpers by playing on the harp. Similarly we become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, Manly by doing Manly acts.

[5] This truth is attested by the experience of states : lawgivers [such as the Spartan Lykourgos, father of the agogé,] make the citizens Manly by training them in habits of right action -- this is the aim of all legislation, and if it fails to do this it is a failure ; this is what distinguishes a good form of constitution from a bad one.

[6] Again, the actions from or through which any virtue is produced are the same as those through which it also is destroyed -- just as is the case with skill in the arts, for both the good harpers and the bad ones are produced by harping, and similarly with builders and all the other craftsmen : as you will become a good builder from building well, so you will become a bad one from building badly.

[7] Were this not so, there would be no need for teachers of the arts, but everybody would be born a good or bad craftsman as the case might be. The same then is true of the virtues. It is by taking part in transactions with our fellow-men that some of us become just and others unjust ; by acting in dangerous situations and forming a habit of fear or of confidence we become Manly or cowardly.

And the same holds good of our dispositions with regard to the appetites, and anger ; some men become temperate and good-tempered, others profligate [promiscuous] and irascible, by actually comporting themselves in one way or the other in relation to those passions.

In a word, our moral dispositions are formed as a result of the corresponding activities.

[8] Hence it is incumbent on us to control the character of our activities, since on the quality of these depends the quality of our dispositions. It is therefore not of small moment whether we are trained from childhood in one set of habits or another ; on the contrary it is of very great, or rather of supreme, importance.

~Aristot. Nic. Eth. 2.1.8, translated by Rackham and myself.

Book II, Chapter 2 :

Right action

[2.2.1] As then our present study, unlike the other branches of philosophy, has a practical aim (for we are not investigating the nature of virtue for the sake of knowing what it is, but in order that we may become good -- Manly -- , without which result our investigation would be of no use), we have consequently to carry our enquiry into the region of conduct, and to ask how we are to act rightly ; since our actions, as we have said, determine the quality of our dispositions.

[2] Now the formula 'to act in conformity with right principle' is common ground, and may be assumed as the basis of our discussion. (We shall speak about this formula later,[a] and consider both the definition of right principle and its relation to the other virtues.)

Footnote:

[a] Prof. Rackham : i.e., in Bk. 6. For the sense in which 'the right principle' can be said to be the virtue of Prudence see 6.13.5 note.

[3] But let it be granted to begin with that the whole theory of conduct is bound to be an outline only and not an exact system, in accordance with the rule we laid down at the beginning, that philosophical theories must only be required to correspond to their subject matter ; and matters of conduct and expediency have nothing fixed or invariable about them, any more than have matters of health.

[4] And if this is true of the general theory of ethics, still less is exact precision possible in dealing with particular cases of conduct ; for these come under no science or professional tradition, but the agents themselves have to consider what is suited to the circumstances on each occasion, just as is the case with the art of medicine or of navigation.

[5] But although the discussion now proceeding is thus necessarily inexact, we must do our best to help it out.

[6] First of all then we have to observe, that moral qualities are so constituted as to be destroyed by excess and by deficiency -- as we see is the case with bodily strength and health (for one is forced to explain what is invisible by means of visible illustrations). Strength is destroyed both by excessive and by deficient exercises, and similarly health is destroyed both by too much and by too little food and drink ; while they are produced, increased and preserved by suitable quantities.

[7] The same therefore is true of Manliness, Temperance, and the other virtues. The man who runs away from everything in fear and never endures anything becomes a coward. Similarly he that indulges in every pleasure and refrains from none turns out a profligate, and he that shuns all pleasure, as boorish persons do, becomes what may be called insensible. Thus Manliness and Temperance are destroyed by excess and deficiency, and preserved by the observance of the mean.

[8] But not only are the virtues both generated and fostered on the one hand, and destroyed on the other, from and by the same actions, but they will also find their full exercise in the same actions. This is clearly the case with the other more visible qualities, such as bodily strength : for strength is produced by taking much food and undergoing much exertion, while also it is the strong man who will be able to eat most food and endure most exertion.

[9] The same holds good with the virtues. We become temperate by abstaining from pleasures, and at the same time we are best able to abstain from pleasures when we have become temperate. And so with Manliness : we become Manly by training ourselves to despise and endure terrors, and we shall be best able to endure terrors when we have become Manly.

Pleasure and

[2.3.1] An index of our dispositions is afforded by the pleasure or pain that accompanies our actions. A man is temperate if he abstains from bodily pleasures and finds this abstinence itself enjoyable, profligate if he feels it irksome ; he is Manly if he faces danger with pleasure or at all events without pain, cowardly if he does so with pain.

In fact pleasures and pains are the things with which moral virtue is concerned.

For pleasure causes us to do base actions and pain causes us to abstain from doing noble actions [καλον].

[2] Hence the importance, as Plato points out, of having been definitely trained from childhood to like and dislike the proper things ; this is what good education means.

~Aristot. Nic. Eth. 2.2.1 - 2.3.2, translated by Rackham and myself.

So :

These are Aristotle's key points regarding the role of habit in inculcating Manliness :

So :

At its most basic, a boy becomes Manly by learning to face pain ; a boy becomes a coward by running away from pain.

That's what happens.

Most of you reading this have spent your lives, in fear, running away from pain -- specifically, the fear engendered by the potential pain of a fist to your face.

As a consequence, you're not Manly ; and you cannot, no matter how hard you try, attract to yourself -- a Man who is Manly.

That's the problem.

You could solve it ; but you're afraid to.

Once again, how does a young person, a young man, a youth -- learn to stand up to blows face to face ?

By standing up to blows face to face.

Functionality and consciousness

Once again :

This, epitomized, is what Aristotle says about how Men achieve the Moral Virtue of Manliness :

By dispositions he means moral dispositions.

Manliness is a moral disposition -- it is the moral disposition to behave in a Manly fashion.

It is the disposition to Fight.

Not to run.

But to Fight.

My work is about Fighting.

Cicero agrees with all of that.

Which is why he says

What is best for Man is that which is desirable in and of itself, has its source in Virtue and is based on Virtue, is of itself praiseworthy, and in fact should be described as the ONLY, rather than the highest, Good :

Manliness.

And every other Roman agrees.

Which is why the great historian of the Roman Revolution, Ronald Syme, says that :

"[At Rome,] Virtus itself stands at the peak of the hierarchy, transcending mores."

~Syme, The Roman Revolution, 1939, 157.

Virtus -- Manliness -- stands at the peak of the hierarchy, transcending all other morals, all other virtues.

The Moral Virtue of Manliness, which is the Ardent Willingness and Requisite Ability to Fight, to Fight Man2Man, and which is the ethikos areté, the Supreme Moral Virtue, the Supreme Ethical Excellence, is, according to Aristotle, primarily about the Man's willingness -- a willingness which is a moral trait -- about the Man's willingness to face pain.

Aristotle :

Though Manliness is concerned with feelings of confidence and fear, it is not concerned with both alike, but more with the things that inspire fear ; for he who is undisturbed in face of these and bears himself as he should towards these is more truly Manly than the man who does so towards the things that inspire confidence. It is for facing what is painful, then, that Men are called Manly. Hence also, then, Manliness involves pain, and is justly [δικαιος] praised ; for it is harder to face what is painful [λυπηρος] than to abstain from what is pleasant.

~Aristot. Nic. Eth. 1117a, translated by WD Ross and myself.

That's Aristotle, who Reasons, and is Supremely Logical, and who values Manliness, and Manly Excellence, which is Manhood, Fighting Manhood.

And I put that discussion of Aristotle in this article because you can't understand what motivated the guys at the Palaistra, without understanding Aristotle, and the Homeric Ethical Code which he followed.

And without understanding Kalon, which is both beautiful and noble, beautiful and honourable.

ARISTOTLE'S

EXCERPTS FROM THE INTRODUCTION ANNOTATED [T]he whole structure [of the Ethics] is coloured by the philosopher's teleological [purposeful] view of nature and of life. It is this that prompts him to base his theory of human conduct on the conception of the Τελος or End ; and the various implications of that conception, related but distinguishable yet not distinguished, do much to guide him to his conclusions.

Τελος -- Telos -- means not only nor primarily aim or purpose, but completion or perfection : the aim of a living organism, the final cause of its being, is to realize the potentiality of its nature, to grow into a perfect specimen of its species.

[Bill Weintraub :

"the aim of a living organism, the final cause of its being, is to realize the potentiality of its nature, to grow into a perfect specimen of its species."

Perfect.

The Purpose of every living organism is to realize the Potentiality of its Nature, to become a Perfect Specimen of its species.

The Aim is to Achieve Perfection.

Classicist Werner Jaeger :

Remember that the Greek for 'good' [agathos] does not merely have the narrow ethical sense we give it, but is the adjective corresponding to the noun areté, and so means 'excellent' in any way. From that point of view ethics is only a special case of the effort made by all things to achieve perfection.

"From that point of view" -- which is the Greek point of view, the Greek Warrior point of view -- "ethics is only a special case of the effort made by all things to achieve perfection."

Which means that Warrior Ethics, which is Manly Ethics, Manly Virtue, Manly Wisdom, and above all, Manly Goodness, is epitomized by Two Men, Two Nude Fighting Men, Struggling to Perfect Their Manly Excellence, Their Fighting Manhood, Their Manliness.

Jaeger says so.

He says that what we call "ethics" is, to the Warrior Greeks, only a special case of the effort made by all things -- to achieve perfection.

Perfection being the Excellence which pertains to each existent thing.

So :

The Excellence of an Eye is Seeing -- what we might call Ocular Excellence.

And the Excellence of an Ear is Hearing -- what we might call Aural Excellence.

While the Excellence of a Man is Manliness and its attendant Fighting -- Fighting With and Against Another Man.

Which we call Manly Excellence.

Which is Manliness.

Manly Excellence is Excellence which is Willing and Able to Fight.

That's what it is, and Jaeger says so :

For, as we've much discussed, Jaeger speaks of "Men Struggling" -- in Fight Agonia -- "to Perfect Their Manhood."

Which of course is Their Fighting Manhood.

Fighting Manhood is the Perfection of a Man.

It's his Excellence.

So -- Jaeger speaks of "Men Struggling to Perfect Their Manhood" -- and that's what Aristotle, whose guide in ethical matters is the Homeric Nobility, that is, the Great Warriors of the Iliad -- that's what Aristotle, per Rackham, is saying : "the aim of a living organism, the final cause of its being, is to realize the potentiality of its nature, to grow into a perfect specimen of its species" :

the aim of the living organism Homo Sapiens, the final cause of its being, is to develop, through strenuous physical struggle, into the perfect specimen of its species -- the Fighting Man, the Warrior, defined and delineated by his Fighting Manhood ]

Rackham :

Hence comes the assumption that not only can conduct or purposive action be centred on a single aim, from which the entire ethical system can be deduced, but also that this aim consists in the full development and exercise in action of man's natural faculties.

[Bill Weintraub :

ie, the full development and exercise in action of the Man's natural faculties as a Fighter, as a Fighting Being]

Rackham :

But again Telos also connotes End in the sense of ultimate point, the last term of a series, the summit and crown of a process. Hence the tendency to think of the End not as a sum of Goods, but as one Good which is the Best. Man's welfare thus is ultimately found to consist, not in the employment of all his faculties in due proportion, but only in the activity of the highest faculty, the 'theoretic' intellect. Not that the lower activities can be dispensed with ; for the philosopher is a man, and must live in the world of men, exercising the Moral Virtues, and the intellectual excellence of Prudence or Practical Wisdom which the Moral Virtues involve. But in strictness the Life of Action has no absolute value ; it is not a part of, but only a means to, the End, which is the Life of Thought.

Yet in the section of the Ethics devoted to the Moral Virtues they are described with an enthusiasm that seems to invest them with a substantive value of their own ; and this especially where the formula of the mean is felt to be inadequate, and is supplemented by the proviso that virtuous actions, to spring from a true habit of virtue, must be done του καλου ενεκα -- for the sake of the moral beauty and rightness of the act itself ; as if moral conduct were not merely a means or an indispensable pre-requisite, but a constituent part, of the Good Life. And the same is true of some places in the essay on Friendship, which is clearly felt not only to facilitate, but to augment and to enhance, the attainment of the End by the individual.

There is here an ambiguity in Aristotle's ethical doctrine which is nowhere cleared up.

Among all the relics of Greek antiquity, Aristotle's Ethics is one of those that retain their interest most freshly. To many readers, new to this kind of study, its application of rigorous logical analysis to the problem of conduct comes as a revelation.* [Footnote: * {Aristotelian} Henry Jackson wrote (Memoir, p 158) : It is an aperient book, if I may use the phrase. I have never forgotten the effect it produced upon me when I was an undergraduate.]

It is true that a moral system which so exalts the life of the intellect is alien in many ways to modern thought and practice ; but in so far as Aristotle's End [Τελος : Completion, Fulfillment, Perfection] can be interpreted less exclusively, and taken to include complete self-development, the full realization in healthy activity of all the potentialities of Man's natural faculties as a Fighter, his teaching has not lost its appeal.

His review of the virtues and graces of character that the Greeks admired stands in such striking contrast with Christian Ethics that this section of the work is a document of primary importance for the student of the Pagan world. But it has more than a historic value. Both in its likeness and in its difference it is a touchstone for that modern idea of the gentleman, which supplies or used to supply an important part of the English race with its working religion.

~H. Rackham, Cambridge, 1926

Bill Weintraub

14 February 2023

© All material Copyright 1997 - 2023 by Bill Weintraub. Agathos, which is often translated as "good," is the adjectival form of the noun Areté / Areta -- Excellence -- which, when referring to a Man, means Manly Excellence which is Manhood, Fighting Manhood -- The Willingness and Ability to Fight.

If Areta is the noun, then, meaning Manhood, meaning the Willingness and Ability to Fight ;

Agathos is the adjective, meaning Manly, meaning Willing and Able to Fight.

Which means that a Manly Man is a Man who's Willing and Able to Fight ;

While Manly Excellence is Excellence which is Willing and Able to Fight, Manly Virtue is Virtue which is Willing and Able to Fight, Manly Goodness is Goodness which is Willing and Able to Fight, and Manly Honour is Honour which is Willing and Able to Fight.

So :

First and foremost, Areté / Areta means Manliness, Manhood, Fighting Manhood, which is the Willingness and Ability to Fight ;

While Agathos is the adjectival form of Areté / Areta, and means Willing and Able to Fight.

At the same time, because Areté / Areta means excellence, Agathos, as the adjectival form of the noun, means excellent, and cannot be understood, when referring to a Man, without reference to Manly Areta which is Manly Excellence, that is, the Sum of All the Corporeal and Mental Excellences of Man :

So:

To the ancient Greek mind, when a Man is described as "agathos," the description carries all these other meanings --

with it.

For all those reasons, the definition of agathos we encourage you to memorize in the Alliance and Ares Is Lord is

When referring to a Man, that's what agathos means, and even when referring to an object, like a Kothon, the word has strong Masculinist and Martial connotations.

In general, in the ancient world, the importance of Fighting Manhood and words which reference Fighting Manhood -- is global.

That said, and arguably :

Since Kalos = Noble and Beautiful ;

We can think of

Agathos as equaling Manly and Excellent.

In both cases, the word means both at the same time :

That is, Kalos doesn't mean Noble or Beautiful -- it means Noble and Beautiful.

And Agathos means Manly and Excellent.

For to an ancient Greek, that which is Manly is also Excellent -- and that goes without saying.

If it's Manly it's Excellent.

Manly and Excellent, therefore, is redundant ; but it's a redundancy which is probably useful and indeed necessary for modern students of the Greeks.

And there's also a corollary from Werner Jaeger which we discuss at length in Understanding the Ethical Supremacy Conferred by Fighting Men and their Fighting Manhood in Chapter X of Biblion Pempton :

[emphasis mine]

Which means that Manly Ethics, Manly Virtue, Manly Goodness, and Manly Honour, is epitomized by the Strenuous Physical Struggle of Two Men to Perfect Their Manly Excellence, Their Fighting Manhood.

Highly Related:

agathos machesthai αγαθος μαχεσθαι : Manly and Excellent at Fighting

Related:

Virtus

ανδρειος

That's Liddell and Scott's definition ; and, Liddell and Scott add,

From the same root [ARES] come areté, ari-, areion [better -- stronger, braver, more Manly], aristos [best -- strongest, bravest, most Manly], the first notion of goodness being that of manhood, bravery in war; cf. Lat. virtus.

Again, that's Liddell and Scott's definition, which is, appropriately, excellent.

In the Alliance and Ares is Lord we define Areté / Areta as Manly Excellence, which is Manliness, which is Manhood, which is Fighting Manhood, which is Manly Goodness, which is Manly Virtue, which is Manly Spirit.

To fully understand Areté / Areta, please read the following discussion :

Bill Weintraub:

Areté is a uniquely Greek word and concept, which, according to classicist CM Bowra, refers to "an intrinsic excellence that exist[s] in all things."

To the Greeks, then, everything has its own intrinsic or inherent excellence, which, however, is latent until such time as it is, and ideally, realized, arrives, or becomes present [paragignomai].

So -- an implement -- such as a drinking cup -- has its own areté.

And so does a body part -- such as an eye.

And so does a Man -- and a Man's soul.

To take an easy example, the areté, that is, the intrinsic or inherent excellence, of an eye is vision, and when the eye sees well, that excellence is present.

Sokrates

~Plat. Alk. 1 133b, translated by Lamb.

The areté -- excellence -- of an eye [ophthalmos] is sight, eyesight, vision [opsis] ; when that excellence is present or realized, the eye is capable of and experiences good vision.

But -- suppose that excellence is not there ?

Sokrates

~Plat. Alk. 1 126b, translated by Lamb.

So : the presence of areté, of excellence, in an eye, is vision -- good vision ; the absence of excellence is blindness.

Similarly for an ear -- the presence or realization of an ear's areté is good hearing ; its absence is deafness.

What about for a Man?

Well, Greek culture is "anthropo-centric," or, really, "andro-centric" -- it centers upon Men.

And that's why Liddell and Scott say, in their definition of Areté, that

And, Liddell and Scott add,

So :

The Excellence of a Man is Manly Excellence, which is Manhood, which consists of valour and prowess, that is, the Willingness and Ability to Fight.

FIGHT.

The Excellence of a Man, his Manly Excellence, is Fighting Manhood.

When speaking of Man, then, and of Man's Soul, there can be no question that to the Greeks, as to us, the Areté / Areta of a Man -- is Manhood.

FIGHTING MANHOOD.

The presence or realization of Manly Excellence is the Adventus -- the arrival -- of Manhood, Fighting Manhood ; its absence is, in Greek, an-andria -- the want or lack of Manhood, UN-manliness.

And un-manliness is as devastating to the human male as blindness to the eye, and deafness to the ear.

Moreover :

When referring to a Man, Areté, one of the most important words in the Greek language, corresponds to the Greek Andreia and the Latin Virtus, both of which are defined as Manliness, Manhood ;

And which have the following attributes :

Again, this definition of the Greek word Andreia and the Latin word Virtus -- and guys, I cannot emphasize this strongly enough -- applies equally to the Greek word Areté:

In sum, Manhood, Valour, Goodness, Virtue, Worth -- Excellence.

Manhood is Valour, Manhood is Goodness, Manhood is Virtue, Manhood is Worth -- Manhood is Excellence.

Manly Excellence which is Fighting Excellence which is Fighting Manhood.

Liddell and Scott :

And, Liddell and Scott add,

Now :

Notice that Liddell and Scott say of Areté that "the first notion of goodness [is] that of manhood, bravery in war" ; and,

that Liddell and Scott define Areté as "goodness, excellence, of any kind, esp. of manly qualities, manhood, valour, prowess (like Lat. virtus, from vir)".

So :

Liddell and Scott twice use the word "goodness" in characterizing Areté, and, not surprisingly, many translators translate the word Areté as Virtue -- and Excellence.

Well, Areté can certainly mean Virtue and Excellence -- but -- what sort of Virtue and Excellence?

Liddell and Scott tell us, and unequivocally :

That of "manhood, bravery in war," they say, and add, "esp. of manly qualities, manhood, valour, prowess (like Lat. virtus, from vir)".

Which means that Areté / Areta, de facto, means Manhood and Manliness, which is the Willingness and Ability to Fight, and that the Virtue and Excellence referred to are attributes of that same Manhood, which, again, is Fighting Manhood.

To better comprehend the relationship between and among Areté / Areta and Andreia and Virtus, please see my brief article titled Understanding the core position and actual meaning of Andreia-Areté-Virtus within the Culture of Fighting Manhood under the Lexicon entry for Andreia.

And also useful is our Discussion of Areté / Areta, which includes a word-by-word dissection of Liddell and Scott's definition, in Chapter III Part I of Biblion Pempton.

Bill Weintraub

Manly is the adjectival form of the noun Manhood.

So :

Strength is the noun.

Strong is the adjective.

Manhood is the noun : The Willingness and Ability to Fight.

Manly is the adjective : Willing and Able to Fight.

Kalon is a very important word for understanding the Greeks, both ethically and aesthetically.

In his translation of Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics, aristotelian H. Rackham renders Kalon as Moral Nobility and says

Καλον is a term of admiration applied to what is correct, especially (1) bodies well shaped and works of art or handicraft well made (see iii. vii. 6), and (2) actions well done ; it thus means (1) beautiful, (2) morally right. For the analogy between moral and material correctness see ii. vi. 9.

[2.6.9] If therefore the way in which every art or science performs its work well is by looking to the mean and applying that as a standard to its productions (hence the common remark about a perfect work of art, that you could not take from it nor add to it -- meaning that excess and deficiency destroy perfection, while adherence to the mean preserves it) -- if then, as we say, good craftsmen look to the mean as they work, and if moral virtue, like nature, is more accurate and better than any form of art, it will follow that moral virtue has the quality of hitting the mean.

~Aristot. Nic. Eth. 2.6.9, translated by Rackham and myself.

Rackham also tell us that Aristotle, in his discussion of specific moral virtues, says that

το καλον -- see Roman numeral III, Arabic numeral 2.

So :

The relationship between Καλον -- Moral Nobility -- and Ανδρεια / Αρετα -- Manliness -- is profound.

In Book III of The Nikomachean Ethics, Aristotle, as part of his extensive discussion of the moral virtue or excellence of Manliness, says,

Though Manliness is concerned with feelings of confidence and fear, it is not concerned with both alike, but more with the things that inspire fear ; for he who is undisturbed in face of these and bears himself as he should towards these is more truly Manly than the man who does so towards the things that inspire confidence. It is for facing what is painful, then, that Men are called Manly. Hence also, then, Manliness involves pain, and is justly [δικαιος] praised ; for it is harder to face what is painful [λυπηρος] than to abstain from what is pleasant.

Aristotle :

[T]he Manly Man is proof against fear so far as man may be. Hence although he will sometimes fear even terrors not beyond man's endurance, he will do so in the right way, and he will endure them as principle dictates, for the sake of what is noble καλον [a]; for that is the end at which virtue aims.

[a] i.e., the rightness and fineness of the act itself, cf. 7.13 ; 8.5,14 ; 9.4 ; and see note on 1.3.2. This amplification of the conception of virtue as aiming at the mean here appears for the first time : we now have the final as well as the formal cause of virtuous action.

Bill Weintraub : The "formal cause" of virtuous action is the individual's "aiming at the mean" between excess and deficiency ; the "final cause" of virtuous action is the individual's decision to act for the sake of what is καλον -- kalon -- that is, what is both Morally Beautiful and Morally Noble.

Which leads us to Prof Rackham's :

Note on 1.3.2 :

Καλον is a term of admiration applied to what is correct, especially (1) bodies well shaped and works of art or handicraft well made (see iii. vii. 6), and (2) actions well done ; it thus means (1) beautiful, (2) morally right. For the analogy between moral and material correctness see ii. vi. 9.

Prof Rackham's point regarding Moral Nobility as the final cause of Virtuous Action is critical to understanding Greek ethical thought and behavior.

Which is why Prof Rackham repeats that point a number of times, saying, for example, that

While aristotelian WD Ross says,

"The motive of Manliness is the sense of Honour."

So :

Καλον means both Moral Nobility -- and Honour.

It is that which is both Right and Fine in and of itself.

Cf. Lat. Honestum

"noble and beautiful"

The word "beautiful" in ancient Greek carries with it the sense of Nobility, of Virtue, of Honour, of Manhood; and "Nobility" in particular means, more often than not, "selflessness."

Again, and this is very important: Nobility, more often than not, means selflessness.

It doesn't mean the House of Lords or guys running around in ermine robes.

It means selflessness.

In addition, because selflessness is noble, it's also honourable.

So that kalos and the related words kalon and kala are also commonly translated as honourable and honour.

AresIsLord.org is a website created and authored by Bill Weintraub.

© All material Copyright 2023 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.

ΗΘΙΚΩΝ

ΝΙΚΟΜΑΧΕΙΩΝ

![]()

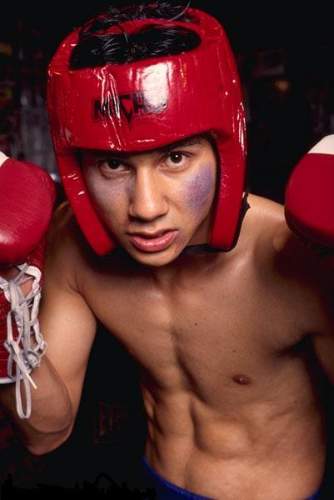

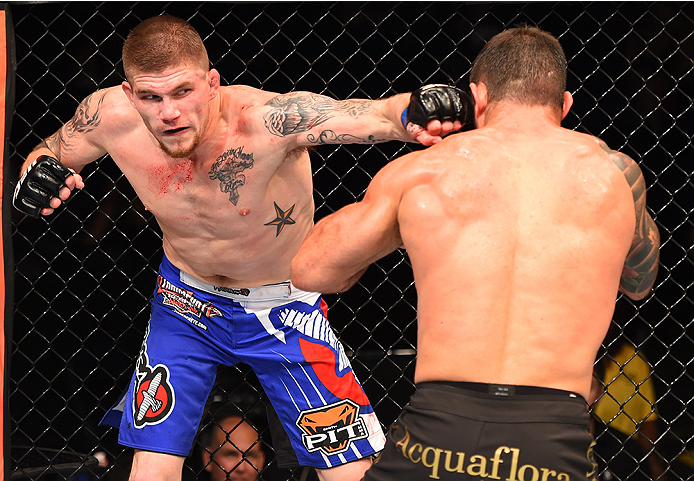

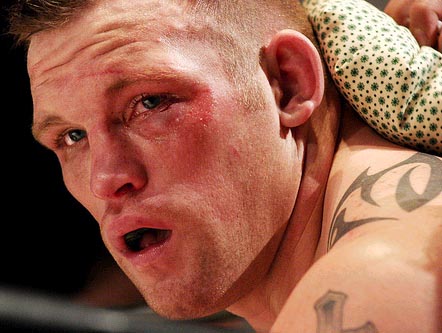

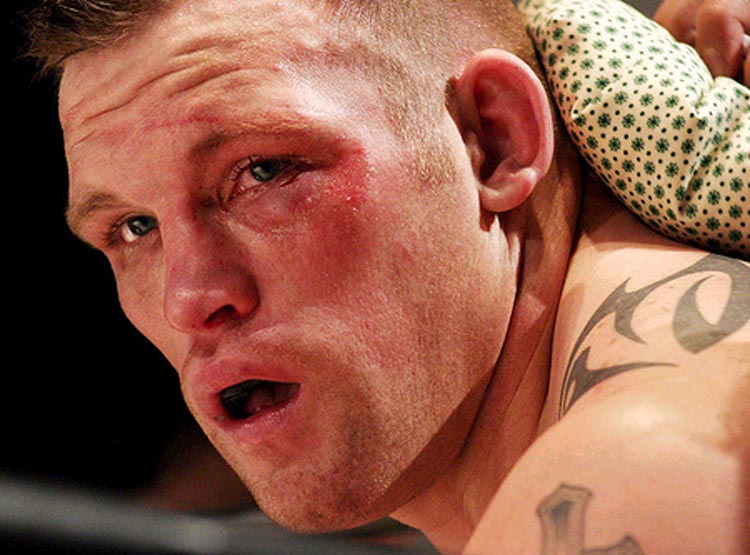

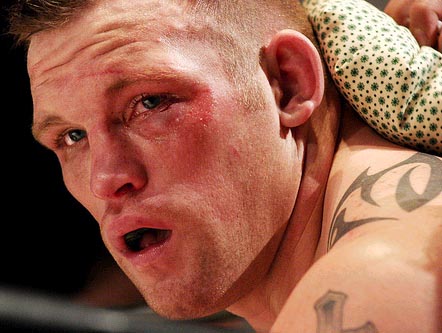

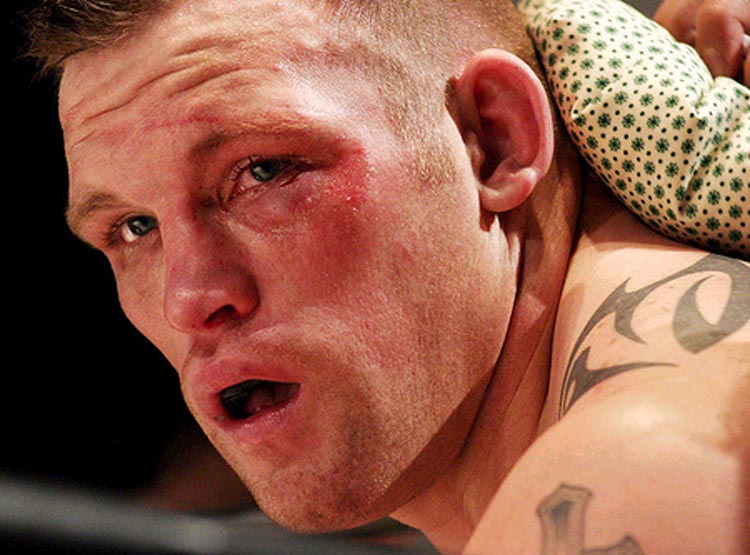

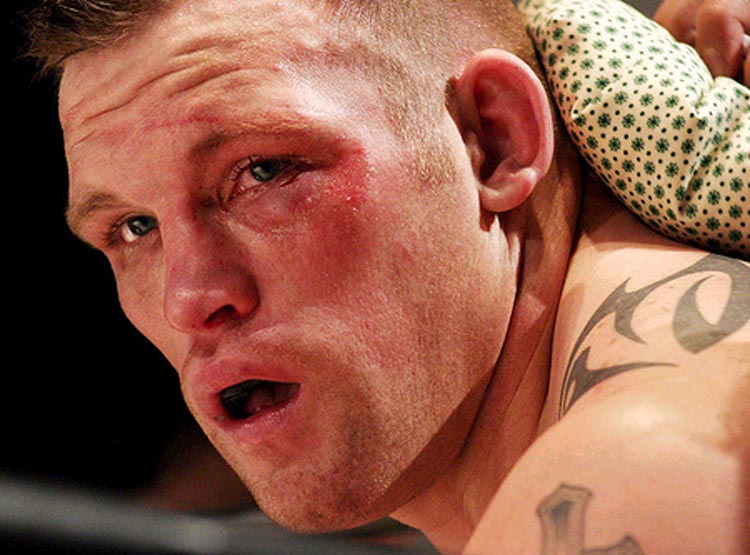

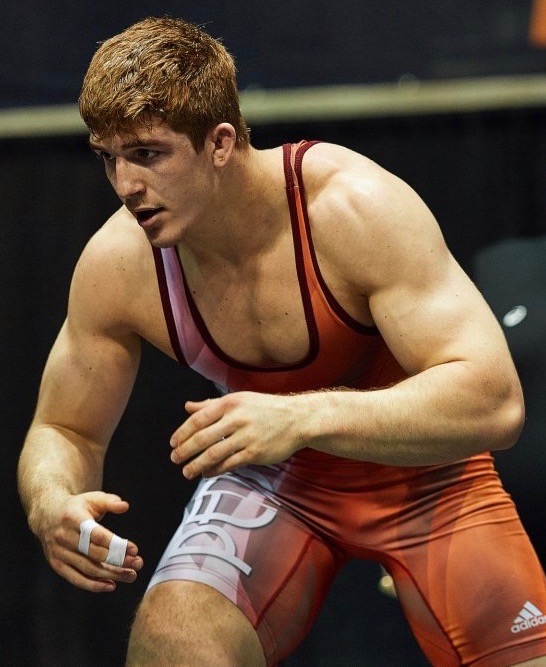

Iconic:

The Pride, the Valour, and above-all Beautiful and Essential Goodness of Men who Fight, and of Fight Itself

Iconic:

See above

The Motive of Manliness is the Sense of Honour

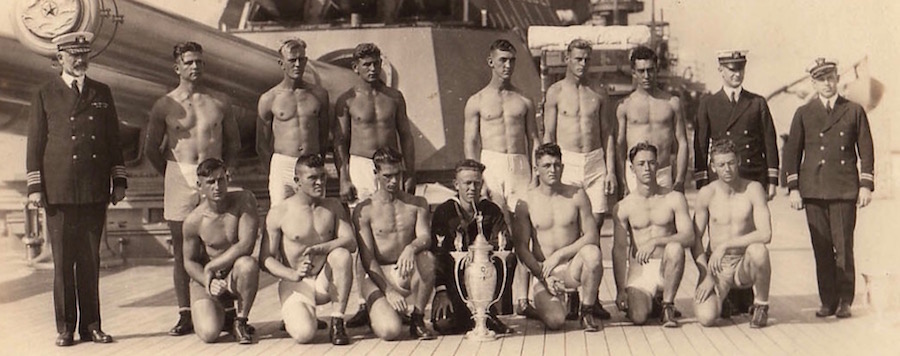

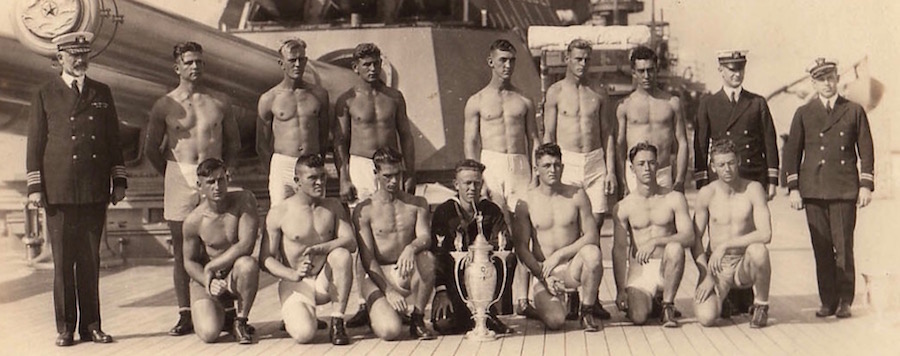

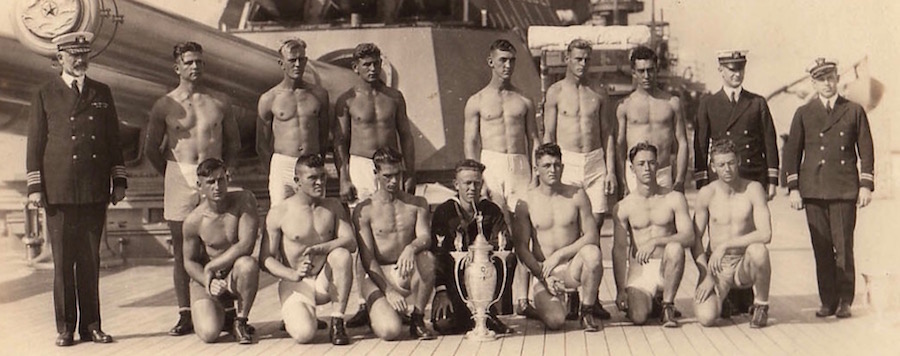

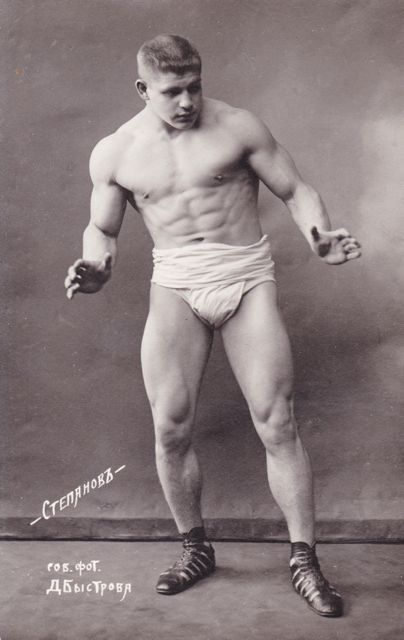

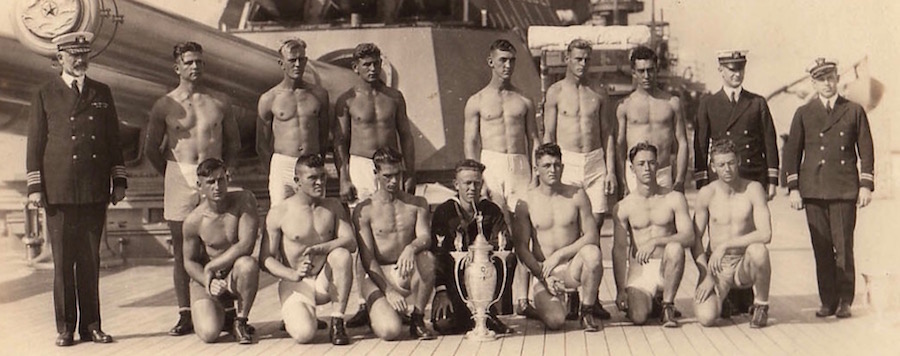

Wrestling Team

USS California

1921-22

Καλος

At Pearl Harbor, 102 Fighting Men

died aboard the USS California,

and 62 more were wounded

Wrestling Team

USS California

1921-22

Καλος

At Pearl Harbor, 102 Fighting Men

died aboard the USS California,

and 62 more were wounded

Wrestling Team

USS California

1921-22

Καλος

At Pearl Harbor, 102 Fighting Men

died aboard the USS California,

and 62 more were wounded

From the same root [ΑΡΗΣ] come areté, areta, ari-, areion [better, more Manly], aristos [best, most Manly], the first notion of goodness being that of manhood, bravery in war; cf. Lat. virtus

Blessedness is not a product of action,

but itself consists in Activity of a certain sort :

It is a Mode of Life.

~Rackham intro xvi

conforms

with Right

Principle

MANLY

pain the test

of Virtue

Far the best for Man is that which is desirable in and for itself, has its source in virtue or rather is based on virtue, is of itself praiseworthy, and in fact I should prefer to describe it as the only rather than the highest good.

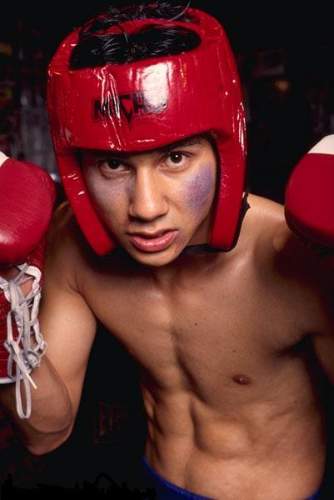

This Man was a Fighter

His nose was broken, his ears battered, his knuckles bruised

This MAN was a FIGHTER

Wrestling Team

USS California

1921-22

Καλος

At Pearl Harbor, 102 Fighting Men

died aboard the USS California,

and 62 more were wounded

ΗΘΙΚΩΝ

ΝΙΚΟΜΑΧΕΙΩΝ

NICOMACHEAN ETHICS

BY

ARISTOTELIAN AND TRANSLATOR H. RACKHAM

BY

BILL WEINTRAUB

![]()

All rights reserved.

Manliness, Manhood : Vigor, strength, might, power, potency ; Valour, gallantry, fortitude ; Virtue, goodness, moral perfection, high character ; Value, worth, merit.

Manliness, Manhood : Vigor, strength, might, power, potency ; Valour, gallantry, fortitude ; Virtue, goodness, moral perfection, high character ; Value, worth, merit --

Manly -- that is, Willing and Able to Fight

Remember that the Greek for 'good' [agathos] does not merely have the narrow ethical sense we give it, but is the adjective corresponding to the noun areté, and so means 'excellent' in any way. From that point of view ethics is only a special case of the effort made by all things to achieve perfection.

![]()

[I]f an eye [ophthalmos] is to see [eidon] itself [autos] it must look at an eye, and at that region [topos] of the eye in which the areté [excellence] of an eye is found to occur ; and this, I presume, is sight [opsis -- eyesight, vision].

[I]f, again, you asked me, "What becomes present in a better [ameinon -- irr. comp. of agathos, which is the adjectival form of Areté -- thus, more excellent] condition of the eyes?" -- I should answer in just the same way, "Sight [opsis] becomes present, and blindness [tuphlotes] absent." So, in the case of the ears [ous], deafness [kophotes] is caused to be absent [apo-gignomai], and hearing [akoe] to

be present [para-gignomai], when they are improved [beltio-o] and getting better treatment.

[Areté is] goodness, excellence, of any kind, esp. of manly qualities, manhood, valour, prowess (like Lat. virtus, from vir)

From the same root [ARES] come areté, ari-, areion [better -- stronger, braver, more Manly], aristos [best -- strongest, bravest, most Manly], the first notion of goodness being that of manhood, bravery in war; cf. Lat. virtus.

Vigor, strength, might, power, potency ; Valour, gallantry, fortitude ; Virtue, goodness, moral perfection, high character ; Value, merit, worth.

Manliness, Manhood : Vigor, strength, might, power, potency ; Valour, gallantry, fortitude ; Virtue, goodness, moral perfection, high character ; Value, merit, worth.

[Areté is] goodness, excellence, of any kind, esp. of manly qualities, manhood, valour, prowess (like Lat. virtus, from vir)

From the same root [ARES] come areté, ari-, areion [better -- more Manly], aristos [best -- most Manly], the first notion of goodness being that of manhood, bravery in war; cf. Lat. virtus.

Aristotle :

where the formula of the mean is felt to be inadequate, it is supplemented by the proviso that virtuous actions, to spring from a true habit of virtue, must be done του καλου ενεκα -- for the sake of the moral beauty and rightness of the act itself

Footnote from Prof Rackham :

Bodies well shaped

and

Actions well done

This statue, the Doryphoros or Spear-bearer,

depicts both the Physical Beauty and Moral Nobility of the

The Doryphoros is an iconic and canonical statue in Greek art

The Warrior represented has perfect proportions

He is both well-shaped and an exemplar of actions well done :

where the formula of the mean is felt to be inadequate, it is supplemented by the proviso that virtuous actions, to spring from a true habit of virtue, must be done του καλου ενεκα -- for the sake of the moral beauty and rightness of the act itself