>

>

AKA

[I]f no one will justly lay to my charge avarice or meanness or lewdness ; if, to venture on self-praise, my life is free from stain and guilt and I am loved by my friends -- I owe this to my father, who, though poor with a starveling farm, would not send me to the school of Flavius [in Venusia, Horace's home town], to which grand boys used to go, sons of grand centurions, with slate and satchel slung over the left arm, each carrying his eightpence on the Ides [a] --

Footnote from Prof Fairclough :

[a] The pupils paid their small school fee on the Ides of each month.

Nay, he boldly took his boy off to Rome, to be taught those studies that any knight or senator would have his own offspring taught.

Anyone who saw my clothes and attendant slaves -- as is the way in a great city -- would have thought that such expense was met from ancestral wealth.

He himself, a guardian true and tried, went with me among all my teachers. Need I say more? He kept me chaste [pudicum -- undefiled] -- and that is manhood's first grace [pudicum, qui primus virtutis honos] -- free not only from every deed of shame, but from all scandal [opprobrio quoque turpi]. He had no fear that some day, if I should follow a small trade as crier or like himself as tax-collector, somebody would count this to his discredit. Nor should I have made complaint, but, as it is, for this I owe him praise and thanks the more.

~Horace, Satires, I.VI, 68-97, translated by Fairclough.

My father kept me chaste, says Horace -- pudicus -- which means undefiled ; and that is Manhood's first grace.

Undefiled means un-penetrated.

And to be un-penetrated is Manhood's first grace.

So :

Chastity is the first grace of Manhood, says Horace.

And Horace goes on to say that by his actions, his father kept him free not only from every deed of shame -- turpis -- ; but from all scandal -- opprobrium.

And we need to understand that turpis also means disgrace, while opprobrium means dishonour.

So Horace's father kept him free not only from every deed of shame and disgrace -- but from dishonour as well.

His father, his guardian, did that by preventing Horace, as a youth in Rome, from being defiled.

Was that an actual danger ?

Yes and Absolutely.

In 88 BC, Venusia, an Italian city and Horace's home town, was taken by the Romans as part of the Social War.

Venusia was sacked, and 3000 of its citizens enslaved -- including Horace's father, who in 88 BC would have been a minor -- a child.

And he was almost certainly raped.

Defiled.

Which was common.

This is what Horace says about the scars and crimes of civil war :

Ah, the shame of our scars and crimes and what brother has done to brother! From what deed have we recoiled in this stony age of ours? What have we left unsullied by our unspeakable wickedness? From what outrage have our young men restrained their hands out of respect for the Gods? What altars have they left undesecrated? O that you would forge afresh your blunted sword on a new anvil and use it against the Massagetae and the Arabs!

~Odes I.XXXV, To the Goddess Fortune, translated by Rudd.

So : Outrage means sexual offense, predation, defilement.

Which happened to Horace's father.

In the wars of the Romans, both civil and foreign, outrage and insult -- acts of sexual viciousness -- were common.

Here, for example, is Tacitus' description of the sack of Cremona, also an Italian city, in 69 AD, during a later period of civil wars :

Cornelius Tacitus :

The Sack of Cremona

Forty thousand armed men burst into Cremona, and with them a body of sutlers and camp-followers, yet more numerous and yet more abandoned to lust and cruelty.Neither age nor rank were any protection from indiscriminate slaughter and violation [stuprum -- defilement, dishonour, disgrace]. Aged men and women past their prime, worthless as booty, were dragged off in wanton insult [ludibrium -- wantonness] to be the soldiers' sport.

Whenever a young woman [a virgin] or handsome youth fell into their hands, they were torn to pieces by the violent struggles of those who tried to secure them, and this in the end drove the despoilers to kill one another.

Men, as they carried off for themselves coin or temple-offerings of massive gold, were cut down by others of superior strength. Some, scorning what met the eye, searched for hidden wealth, and dug up buried treasures, applying the scourge and the torture to the owners. In their hands were flaming torches, which, as soon as they had carried out the spoil, they wantonly hurled into the gutted houses and plundered temples.

In an army which included such varieties of language and character, an army comprising Roman citizens, allies, and foreigners, there was every kind of lust, each man had a law of his own, and nothing was forbidden.

For four days Cremona satisfied the plunderers. When all things else, sacred and profane, were settling down into the flames, the temple of Mephitis outside the walls alone remained standing, saved by its situation or by divine interposition.

~Tac. Hist. 3.33, translated by Church and Brodribb.

"In an army . . . comprising Roman citizens, allies, and foreigners, there was every kind of lust, each man had a law of his own, and nothing was forbidden."

That was as true in 69 AD as it had been in 88 BC.

Horace's father was raped, defiled, deprived of his chastity.

Following his capture and rape, Horace's father was a slave -- for a time.

Eventually, he was emancipated, that is, given his freedom, and was then known as a freedman.

And he was a freedman when Horace was born in 65 BC.

Horace therefore was known as the son of a freedman -- libertino patre natum -- "born of a freedman father."

Not the same as being born the son of a knight or senator [eques atque senator prognatos].

Nevertheless, Horace's father was determined that Horace would receive the same education -- as did the sons of knights and senators.

Not the education open to him in the small town of Venusia, in a school attended by the sons of centurions -- but the education available to him in the great city of Rome, in a school attended by the sons of knights and senators.

With that as his goal, Horace's father moved himself and his son to Rome --

And enrolled Horace in a fashionable school.

Horace would have turned 20 in 45 BC.

So he would have been going to school in Rome sometime in the 50s BC -- from, let's say, ca 58 to 47 BC -- from the age of seven to eighteen.

During which the city was greatly troubled :

At that time (the 50's) Rome was plagued by gang warfare between Caesarians (led by Clodius) and Pompeians (led by Milo), which eventually led to the civil war (49-45).~Introduction to Horace's Odes, edited and translated by Rudd.

So :

In the 50s BC there was intense street-fighting in Rome between two gangs, one loyal to Julius Caesar and the other loyal to Pompey the Great.

Caesar's gang was led by Clodius -- who was truly odious -- and Pompey's by Milo.

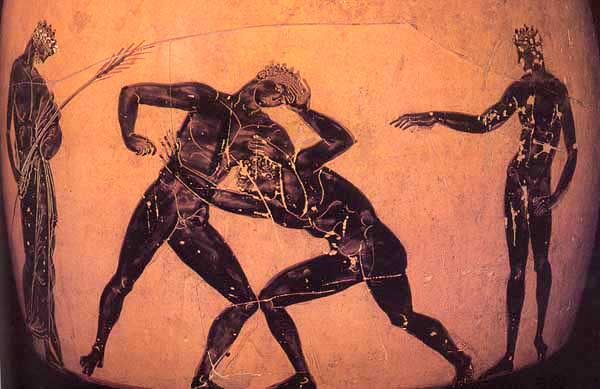

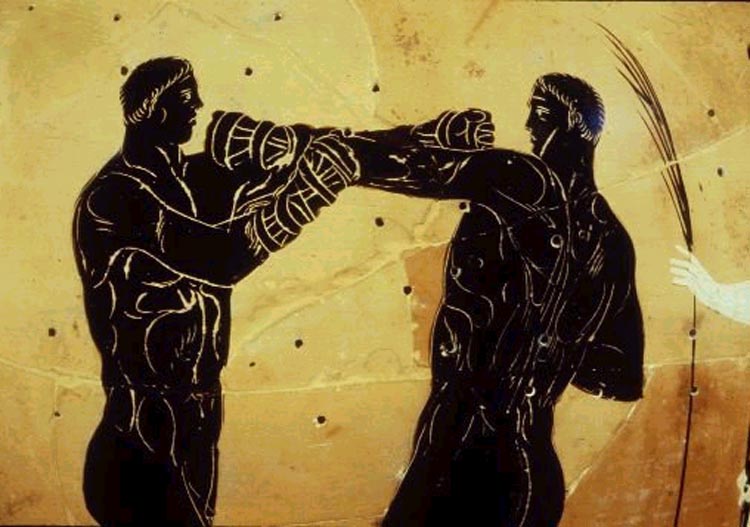

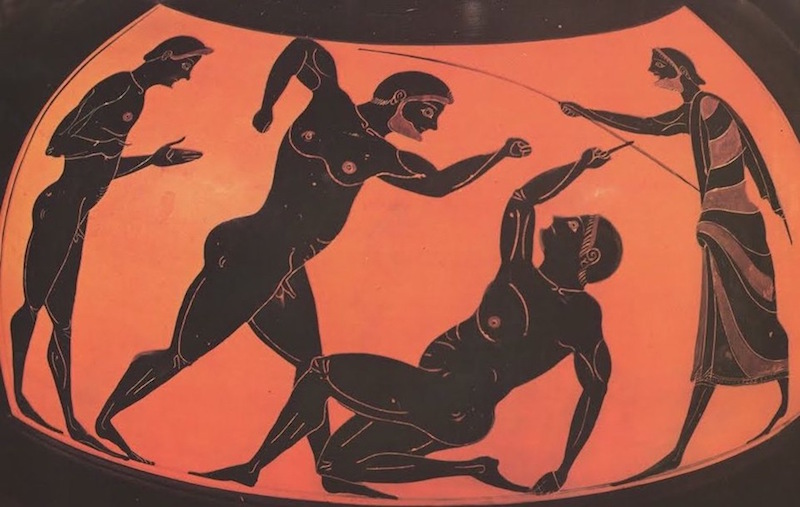

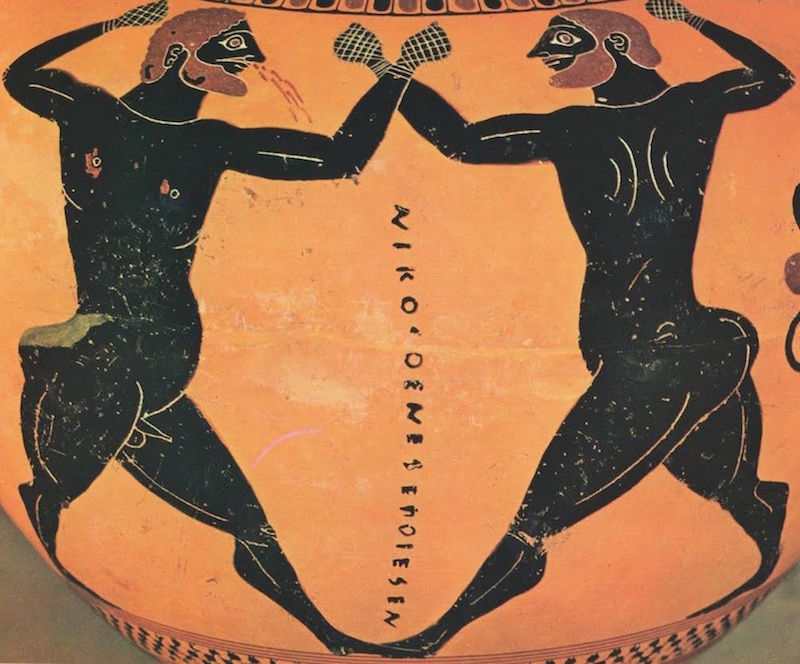

Both Clodius and Milo had hired Gladiators to Fight for them -- Gladiators bought and brought out of the arenas and into the streets.

Eventually, Milo's Gladiators succeeded, in a street brawl, in killing Clodius.

Milo was tried for that killing by the Senate -- and although Cicero tried, he couldn't save Milo, who was exiled.

Rome was a dangerous place.

And Horace's father knew all too well what could happen to a child alone in the streets.

So he went with his son "among all his teachers."

And guarded him.

He kept him pudicus -- chaste, undefiled -- which is, Horace tells us, the first grace of Manhood -- primus virtutis honos.

And, says Horace, for this I owe my father praise and thanks the more -- [laus illi debetur et a me gratia maior].

The excellent education Horace received in Rome enabled him, when he was old enough, to study in Athens :

In his nineteenth year or thereabouts (i.e. about 46 BC) Horace went to Athens to add the finishing touches to his education by the study of philosophy. The Greek poets also largely occupied his attention at this time. Among his friends during this Athenian period may be mentioned the young Cicero, son of the orator, and M. Valerius Messalla, who, with many other young Romans, were residing at Athens for the purpose of study.~CE Bennett, "Life and Works of Horace," in Horace, Odes and Epodes, 1912.

That education was, again, paid for by his father.

The excellent education Horace received at Rome and Athens, combined with his inborn poetic talent and his social skills, including, in an age which highly valued friends, what was obviously a superb gift for friendship -- enabled Horace to rise from "son of a freedman father" to intimate friend of the Emperor Augustus -- and other high-born and/or talented Romans, including Agrippa, Pollio, Virgil, Varius, and Maecenas.

Maecenas, a wealthy and aristocratic Etruscan who was one of the first Italians to support Augustus, was initially Horace's patron.

But over time, the high-born Maecenas and the low-born Horace became close friends.

Very close friends.

In fact, in one of his published odes, Horace said that he didn't want to outlive Maecenas -- and that he wouldn't :

Alas, if some untimely blow snatches thee, the half of my own life, away, why do I, the other half, still linger on, neither so dear as before nor surviving whole ? That fatal day shall bring the doom of both of us. No false oath have I taken ; both, both together, will we go, whene'er thou leadest the way, prepared as comrades to travel the final journey.~Odes, II.XVII -- the classy translation is by CE Bennett, 1912.

"Both, both together, will we go, whene'er thou leadest the way, prepared as comrades to travel the final journey," says Horace.

And, also in fact, Maecenas died in September of 8 BC, and Horace followed just a couple months later ; the two Men were buried near each other on Rome's Esquiline Hill.

It's astonishing how far Horace traveled in his life -- and much of that was due to his father.

Who must have been an extraordinary person.

That extraordinary Man, Horace's father, died sometime during Horace's stay in Athens, and long before Horace achieved success.

This is what the Greco-Roman intellectual Plutarch says about ancient fathers and their love for their sons at a time when life was far shorter than it is now :

He that plants a vineyard in the vernal equinox gathers the grapes in the autumnal ; he that sows wheat when the Pleiades set reaps it when they rise ; cattle and horses and birds bring forth young at once ready for use ; but as for man, his rearing is full of trouble, his growth is slow, his attainment of excellence is far distant and most fathers die before it comes.Neocles did not live to see the Salamis of Themistocles nor Miltiades the Eurymedon of Cimon ; nor did Xanthippus ever hear Pericles harangue the people, nor did Ariston hear Plato expound philosophy ; nor did the fathers of Euripides and Sophocles come to know their sons' victories ... .

~Plutarch, De Amore Prolis, 4, translated by Helmbold.

Nor did Horace's father live to see his son become a famous and revered Roman poet.

But Horace never forgot his father, and the care he'd taken with his son's upbringing and education.

Prof Bennett says that that upbringing and education "evidently involved no little personal and financial sacrifice on the father's part -- a sacrifice appreciated to the full by Horace" :

In a touching passage almost unique in ancient literature (Sat. I.VI, 72 ff) the poet tells us of the father's devotion ... . Ambitious only for his son's mental and moral improvement, without a thought of the larger material prizes of life, he not only provided Horace with the best instruction the capital afforded, but watched with anxious care over the boy's moral training as well, even accompanying him to school and back again to his lodgings.

The story of Horace and his father, which continues below, is yet another striking tale of male-male devotion in the ancient world.

Horace's father didn't live to see his son's success, but his son lived to memorialize his father's devotion -- in glowing verse, which is still read today.

Bill Weintraub

June 3, 2021

In Satire I.IV, Horace speaks of how his father gave him moral instruction through example :

If in my words I am too free, perchance too light, this bit of liberty you will indulgently grant me.'Tis a habit the best of fathers taught me, for, to enable me to steer clear of follies, he would brand them, one by one, by his examples.

Whenever he would encourage me to live thriftily, frugally, and content with what he had saved for me, "Do you not see," he would say, "how badly fares young Albius, [a] and how poor is Baius? A striking lesson not to waste one's patrimony!"

Footnote from Prof Fairclough :[a] The extravagance of Albius, who, we've learned earlier, "dotes on bronzes," impoverishes his son, young Albius.

When he would deter me from a vulgar amour, "Don't be like Scetanus."

And to prevent me from courting another's wife, when I might enjoy a love not forbidden, "Not pretty,'" he would say, "is the repute of Trebonius, caught in the act [non bella est fama]."

"Your philosopher will give you theories for shunning or seeking this or that : enough for me, if I can uphold the rule our fathers have handed down [traditum ab antiquis morem], and if, so long as you need a guardian, I can keep your health and name from harm. When years have brought strength to body, and mind, you will swim without the cork."

With words like these would he mould my boyhood [puerum] ; and whether he were advising me to do something, "You have an example for so doing," he would say, and point to one of the special judges [iudicibus selectis] [b] ;

Footnote from Prof Fairclough :[b] A reference to the list of jurors, men of high character, annually empanelled by the praetor to serve in the trial of criminal cases.

; or were forbidding me, "Can you doubt whether this is dishonourable and disadvantageous [inhonestum et inutile] [c] or not, when so and so stands in the blaze of ill repute?"

Footnote from Bill Weintraub :[c] In-honestum et inutile = dishonourable and inexpedient. Dishonourable also means immoral -- so what Horace's father is saying is that the act in question is immoral, dishonourable, inexpedient. Those are categories Cicero discusses in his book de Officiis -- Regarding Moral Duties -- and derive from both Stoicism and, as Horace's father says, the common usage and customs of the Roman community as transmitted from father to son.

Note also that the wrong-doer "stands in the blaze of ill repute."

And that's as Prof Lendon says in his study of honour and shame in Imperial Rome --

Indeed, the greater a man's honour, the higher his position in society, the more people watched him, and the more he felt his actions hemmed in by his own rank.It was signally disgraceful -- especially destructive of honour -- for a nobilis, one of the highest born in Roman society, to waste his fortune, or to be morally vicious, because of the 'bright light' his ancestry held over him.

~Empire of Honour, pb, 2001, 39.

Horace :

As a neighbour's funeral scares gluttons when sick, and makes them, through fear of death, careful of themselves, so the tender mind is oft deterred from vice [vitium] by another's shame [opprobrio -- dishonour].

Thanks to my father's training I am free from vices [vitiis] which bring disaster, though subject to lesser frailties such as you would excuse.

And, Horace adds,

Perhaps even from these much will be withdrawn by time's advance, candid friends, self-counsel ; for when my couch welcomes me or I stroll in the colonnade [d], I do not fail myself : "This is the better course : if I do that, I shall fare more happily : thus I shall delight the friends I meet : that was ugly conduct of so and so : is it possible that some day I may thoughtlessly do anything like that?" Thus, with lips shut tight, I debate with myself ; and when I find a bit of leisure, I trifle with my papers [e].Footnotes from Prof Fairclough :[d] The colonnades, or porticoes, were a striking architectural feature of ancient Rome, and much used for promenading in. The lectulus was an easy couch for reclining upon while reading, corresponding to our comfortable arm-chairs.

[e] Horace toys with his papers by jotting down his random thoughts.

~Satires, I.IV, 103-139, translated by Fairclough, 1926.

Bill Weintraub :

The moral teaching presented by Horace's father is very Roman -- it has, as the great nineteenth-century Latinist Harry Thurston Peck says, a "predominant tone of sober directness and moral strength" ;

It displays little interest in ethical theory or philosophy, being instead, as Walter Miller says, "Intensely, narrowly, practical" ;

It's traditional and patriarchal, it is, as Horace's father, "the best of fathers," declares, "the rule, the tradition, the mores, our fathers have handed down [traditum ab antiquis morem]" -- ;

And, as we would expect in an Honour Society, it focuses on Honour and dishonour :

"Can you doubt whether this is dishonourable and disadvantageous [inhonestum et inutile] or not, when so and so stands in the blaze of ill repute?"

Again, the price of immorality is dishonour, which surrounds the evil-doer in a "blaze of ill repute [flagret rumore malo]."

So that, Horace concludes, thanks to my Father's training, when I was a boy, my tender mind was "deterred from vice" ; and as an adult, I'm free from those "vices which bring disaster."

Vice, vitium -- is the opposite of Virtue -- Virtus.

Virtus brings Honour ; vice brings dishonour.

In an Honour Society, then, all Men seek Honour ;

All Men fear dishonour ;

All Men expect the strict return of a favour, for that alone is honourable ;

And all Men seek to punish an insult -- an outrage -- to their Honour -- usually through physical violence.

And that's why Horace speaks of "vices which bring disaster."

Again :

Virtus brings Honour ; vice brings dishonour and with it disaster.

Bill Weintraub

June 5, 2021

AENEAS prays to the CUMAEAN SYBIL :

"For me no form of toils arises, O maiden, strange or unlooked for ; all this have I foreseen and debated in my mind. One thing I pray : since here is the famed gate of the nether King, and the gloomy marsh from Acheron's overflow, be it granted me to pass into my dear father's sight and presence ; show the way and open the hallowed portals! Amid flames and a thousand pursuing spears, I rescued him on these shoulders, and brought him safe from the enemy's midst. He, the partner of my journey, endured with me all the seas and all the menace of ocean and sky, weak as he was, beyond the strength and portion of age. He it was who prayed and charged me humbly to seek you and draw near to your threshold. Pity both son and sire, I beseech you, gracious one ; for you are all-powerful, and not in vain did Hecate make you mistress in the groves of Avernus."

Roman sons were expected to care for and, if need be, avenge their sires.

Cicero :

The great talents of Lucius Lucullus and his great devotion to the best sciences, with all his acquisitions in that liberal learning which becomes a person of high station, were entirely cut off from public life at Rome in the period when he might have won the greatest distinction at the bar. For when as quite a youth, in co-operation with a brother possessed of equal filial affection and devotion, he had carried on with great distinction the personal feuds of his father,[1] he went out as quaestor to Asia, and there for a great many years presided over the province with quite remarkable credit . . .Footnote from Prof Rackham :[1] The elder Lucullus had been tried and found guilty of misconduct when commanding in the slave-war in Sicily, 103 b.c. His sons (in accordance with the Roman sentiment of filial duty) did their best to ruin his prosecutor Servilius.

So :

At Rome, "filial affection and devotion," that is, "the Roman sentiment of filial duty," required a son or sons to do their best to ruin those who had prosecuted their father.

And sometimes, it's a simple passage like this one in Cicero, which opens our eyes to a simple truth, which may previously have eluded us.

Many historians, and ordinary people as well, have wondered at the single-minded and indeed often fanatical spirit in which Octavian, who after 27 BC was Augustus, undertook, starting in 44 BC, to avenge the murder of his great uncle -- and adoptive father -- Julius Caesar.

And to assume the office which Caesar had bequeathed him.

But the reason is plain.

Julius Caesar was Octavian's adoptive father.

And Octavian's loyalty to Caesar was very great, as would have been the case with any Roman son and his father, adoptive or otherwise.

Octavian/Augustus' moral beliefs were not complex.

Prof Rudd summarizes them as :

the traditional values of courage, constancy, loyalty, and piety

That is, Virtus, Fortitudo, Fides, and Pietas.

Like Horace's, those were the traditional Roman beliefs handed down, in true patriarchal fashion, from father to son.

Rome was intensely patriarchal.

As was Octavian's moral compass.

Octavian set out to avenge Caesar and assume the mantle of Augustus because that's what "the Roman sentiment of filial duty" required.

All the blood spilled and treasure spent between 44 and 30 were done so in the spirit and fulfillment of "filial affection and devotion."

Octavian cared about his adoptive father.

He'd lost his natural father, Gaius Octavius, to natural causes.

Now his adoptive father, who'd promised him great things, had been murdered.

Octavian -- who became Augustus in 27 BC -- saw to it that he was avenged, and that his father's power -- passed to him.

In 2 BC, Augustus completed the Temple of Mars Ultor -- Mars the Avenger -- which included a statuary group of Mars, Venus, and Caesar.

Mars was the father of the Roman people, Venus was the mother of Aeneas and the grandmother of Julus, and Julius Caesar was Julus' direct descendant.

Again, Roman values were not complex.

The Romans were, as Prof Lendon says, "a martial people governed by a Warrior aristocracy."

Here, for example, is Cicero talking about duritiam virilem -- Manly Hardness :

ON

MANLY HARDNESS

Virilis Duritia = Manly Hardness, Manly Toughness

nec vero illa sibi remedia comparavit ad tolerandum dolorem, firmitatem animi, turpitudinis verecundiam, exercitationem consuetudinemque patiendi, praecepta fortitudinis, duritiam virilem

~Cicero, Tusculan Disputations, V.74

Michael Grant :

The real remedies for pain -- moral force, distaste for moral wrongdoing and dishonour, constant practice in endurance and fortitude, manly toughness [duritiam virilem] -- these are all things that Epicurus [a hedonist] has not bothered to acquire.

JE King :

Aids to the endurance of pain can be found in strength of soul, shame of baseness, the habitual practice of patience, the lessons of fortitude, a manly hardness . . .

~Cic. Tusc. V.74, translated by Grant and King

So, says Cicero, the real remedies for pain are moral force, distaste for moral wrongdoing and dishonour, constant practice in endurance and fortitude, manly hardness.

Not complicated.

And constantly reinforced by potent cultural messages :

753 BC Founding of Rome

509 BC Expulsion of the kings

450 BC Twelve Tables of Roman law

390 BC Gauls capture Rome

289 - 275 BC War with Pyrrhus ; Rome's victory over Pyrrhus reveals, to a surprised world, the superiority of the Roman legion

264 - 241 BC 1st Punic War (Carthage)

219 - 292 BC 2nd Punic War

149 - 146 BC 3rd Punic War ; the Roman victor is Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus Africanus -- Scipio Africanus Minor -- who in his private life champions the work of the Stoic Panaetius, who in turn is a major influence on the philosophic works of Cicero, including the de Re Publica, de Legibus, and de Officiis

Prof Rudd :Eleven of the eighty-eight pieces in Books I-III of Horace's Odes are public poems on patriotic themes, upholding the traditional values of courage, constancy, loyalty, and piety which the new (Augustan) regime was keen to restore. These values had been articulated and confirmed in the kind of Stoicism brought to Rome in the mid second century by the Greek Panaetius, and transmitted to later generations by Cicero.

109 BC Atticus is born

Prof Falconer :Cicero's Cato Maior de senectute and the Laelius de amicitia are both dedicated to Titus Pomponius Atticus, who was born at Rome in 109 b.c. His friendship with Cicero began in childhood and continued until Cicero's death in 43 b.c. From about 88 to 65 b.c, Atticus lived in Athens, devoting himself to the study of Greek philosophy and literature. He wrote Latin verses, which are highly commended by his biographer Cornelius Nepos, Roman Annales, a genealogical history of Roman families and a history in Greek of Cicero's consulship. He died in 32 b.c, at the age of 77, highly esteemed by the Emperor Augustus Caesar and by the leading Romans of his day. More than 400 letters from Cicero to him are extant to prove the rare intimacy and deep affection existing between these two remarkable men.

106 BC Cicero is born

91 - 88 BC The Social Wars between Rome and her allies

88 BC Venusia is sacked by the Romans and 3000 prisoners are taken, among them Horace's father

88 - 66 ?? BC Horace's father is enslaved and then emancipated

70 BC Virgil is born

65 BC Horace is born

63 BC Octavian -- later Augustus -- is born ; Cicero is consul at Rome

58 - 47 BC Horace is educated at Rome

50 - 30 BC Rome is embroiled in civil war after civil war.

Tacitus :Force was his [Pompey's] means of control, and by force he lost it.In the twenty years of civil strife that followed, law and morality were non-existent, criminality went unpunished, decency was often fatal.

48 BC Julius Caesar is victorious in his war with Pompey -- the Republic is greatly diminished in power -- Caesar becomes dictator

46 BC Horace goes to Athens for further education

46 - 44 BC Cicero writes the bulk of his philosophic works, including The Tusculan Disputations

Prof Falconer :Full of grief for the downfall of the Republic, harassed by debt and struggling under an almost intolerable weight of domestic sorrows, he turned to the writing of philosophic books as the surest relief from trouble and as the best means of serving his country. Early in 46 b.c., he withdrew from Rome to the quiet of his country places, and in that year published Paradoxa, Partitiones oratoriae, Orator, De claris oratoribus, and, probably, Hortensius.

In February 45 the death of his adored and only daughter drove him into a frenzy of writing in an effort to forget his grief. In an incredibly short time he produced, in the years 45 and 44, Consolatio, De finibus, Tusculanae disputationes, De natura deorum, Cato Maior, De divinatione, De fato, De gloria, De amicitia, Topica, and De officiis. The De officiis, finished in November, closed his literary career.

44 BC Julius Caesar is assassinated ; the 18-year-old Octavian, Caesar's great-nephew, asserts that he and he alone is Caesar's heir

43 BC The Triumvirate (Mark Anthony, Octavian, Lepidus) seizes power ; Cicero is proscribed and executed by the Triumvirs

42 BC Horace fights for the Republic at Philippi ; the Republic is defeated ; Horace barely escapes with his life

Prof Syme :After a tenacious and bloody contest, the Caesarian army prevailed. Once again the Balkan lands witnessed a Roman disaster and entombed the armies of the Republic -- Romani bustum Populi. This time the decision was final and irrevocable, the last struggle of the Free State. Henceforth nothing but a contest of despots over the corpse of liberty. The men who fell at Philippi fought for a tradition, a principle and a class -- narrow, imperfect and outworn, but for all that the soul and spirit of Rome.

42 BC Horace is exiled and his patrimony confiscated by the Triumvirs

41 BC Horace is amnestied and returns to Rome, finding work as a scribe

40 BC Horace meets Virgil and other Roman poets, including Varius and Plotius ; Horace and Virgil are soon warm friends, for Horace in particular has a great gift for friendship, and cherishes his friends :

Most joyful was the morrow's rising, for at Sinuessa there meet us Plotius, Varius, and Virgil, whitest souls earth ever bore, to whom none can be more deeply attached than I. O the embracing! O the rejoicing! Nothing, so long as I am in my senses, would I match with the joy a friend may bring.Satires I.V.39-44, A Journey to Brundisium, translated by Fairclough

40 BC Horace begins his career as a Roman poet

39 - 38 BC Horace is introduced to Maecenas, a very wealthy and intimate friend and advisor of Octavian (after 27 BC, Augustus), and patron of the arts, esp poetry ; at first patron and client, Horace and Maecenas eventually become close friends

35 BC Virgil publishes the Eclogues

34 - 33 BC Maecenas gives Horace the Sabine Farm, making him financially independent

31 BC Rome -- in the person of Octavian -- is triumphant at Actium

30 BC Octavian takes Alexandria

30 BC Horace publishes Bk I of the Satires, including I.IV -- Thanks to My Father's Training ; and I.VI -- Chastity, the First Grace of Manhood : poems which celebrate Horace's manly education by "the best of fathers"

29 BC Horace publishes the Epodes ; Virgil publishes the Georgics

27 BC Octavian is named Augustus by an Act of Settlement of the Senate, and becomes the unquestioned Princeps -- "First Man" -- of the Roman state and people, who thus exchange Libertas -- for Pax ; like Virgil's, Horace's relations with Augustus are described as "intimate and cordial"

27 BC Augustus encourages Virgil to write an epic poem about Aeneas, a Trojan Warrior who helped found Rome and was the father of Julus, the progenitor of the Julian clan

25 BC Horace publishes Bk II of the Satires

23 BC Horace publishes Bks I - III of the Odes, including III.II, Endurance and Fidelity :

Dulce et Decorum est Pro Patria Mori :

It is Sweet and Fitting to Die for Fatherland.

Yet Death o'ertakes not less the runaway,

nor spares the limbs and coward backs

of unwarlike youths.[Mors et fugacem persequitur virum,

nec parcit imbellis iuventae

poplitibus timidove tergo.]

20 BC Horace publishes Bk I of the Epistles

19 BC Virgil dies ; the Aeneid is not yet finished, and Virgil wants it destroyed, but Augustus orders it saved and has it published

17 BC Horace is chosen to write the Carmen Saeculare -- Hymn for a New Age -- by Augustus ; it's performed in Rome by a chorus of chaste boys and virginal girls :

Whence, in company with chaste boys, would the unwedded maid learn the suppliant hymn, had the Muse not given them a bard? [ll. 132-3]

Their chorus asks for aid and feels the presence of the Gods, calls for showers from heaven, winning favour with the prayer he has taught, averts disease, drives away dreaded dangers, gains peace and a season rich in fruits. Song wins grace with the Gods above, song wins it with the Gods below. [ll. 134-7] [a]

Footnote from Prof Fairclough :

[a] In ll. 132-133, Horace is thinking chiefly of the chorus of chaste boys and maiden girls who sang the Carmen Saeculare in 17 b.c. ; in ll. 134-137, he sets forth the function of the chorus, especially in association with religious ceremonies.

~Horace, Epistles II, Book II, To Augustus, translated by Fairclough.

14 BC Horace publishes Bk IV of the Odes

13 BC Horace publishes Bk II of the Epistles

8 BC Maecenas dies in September ; Horace dies 8 weeks later

'Tis the will neither of the Gods nor of myself that I should pass away before thee, Maecenas, the great glory and prop of my own existence.

Alas, if some untimely blow snatches thee, the half of my own life, away, why do I, the other half, still linger on, neither so dear as before nor surviving whole ? That fatal day shall bring the doom of both of us. No false oath have I taken ; both, both together, will we go, whene'er thou leadest the way, prepared as comrades to travel the final journey.

RECOMMENDED POEMS :

ENDURANCE AND FIDELITY

THE FEATS OF DRUSUS

IN PRAISE OF LOLLIUS

ENDURANCE, AND FIDELITY TO ONE'S TRUST

JUSTICE, AND STEADFASTNESS OF PURPOSE

POETIC AND POLITICAL HARMONY

RELIGION AND PURITY

POOR NEOBULE

POMPEIUS' RETURN

DESPAIR NOT MAECENAS / ONE STAR LINKS OUR DESTINIES

Prof Rudd :

[While Horace was still in Athens, Caesar was assassinated in Rome], after which Brutus left Italy to raise an army [for the Republic] in the East. In Athens he recruited Horace, who was attending university in Athens along with several young aristocrats.

Despite his lack of experience Horace was made a military tribune, and before long took part in the disastrous battle of Philippi on the Via Egnatia in Macedonia (42 b.c.). [The forces of Antony and Octavian] won the day, and Horace was lucky to escape with his life. Returning to Rome under an amnesty, he managed to acquire a secretaryship in the treasury. This gave him enough to live on, and he began to write poetry in earnest.

Soon, on the strength of some early epodes and satires, Vergil and Varius introduced him to Maecenas, and he entered the great patron's circle early in 37 bc. In that year Horace accompanied Maecenas on a journey south (Sat. I.5). He was also probably with him when, in the struggle against Sextus Pompeius, Octavian's fleet suffered a serious setback off Cape Palinurus (Odes III.4.28). Later he affirmed his willingness to accompany Maecenas to Actium (Epod. 1), and may actually have done so (Epod. 9). If he did, that would have added further force to Odes II.6.7-8, where in addressing an old comrade-in-arms he claims to be "weary of the sea and marching and fighting." So, like many others who grew up in the last generation of the Republic, Horace was all too familiar with death and danger. Perhaps that was one reason why he felt such an affinity with the old warrior Alcaeus [the great Greek lyric poet, who'd lived ca 600 bc].

Bill Weintraub :

"Like many others who grew up in the last generation of the Republic, Horace was all too familiar with death and danger."

Actually, that common and close familiarity with danger and death had become the norm long before the fall of the Roman Republic in 42 bc -- it had started with the death of Alexander in 323 and Aristotle in 322.

Prof Rackham :

Alexander the Great died in 323 and Aristotle in 322 b.c. Both Epicurus and Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, began to teach at Athens about twenty years later. The date marks a new era in Greek thought as in Greek life. Speculative energy had exhausted itself ; the schools of Plato and Aristotle showed little vigour after the death of their founders. Enlightenment had undermined religion, yet the philosophers seemed to agree about nothing except that things are not what they appear ; and the plain man's mistrust of their conclusions was raised into a system of Scepticism by Pyrrho.

Meanwhile the outer order too had changed. For Plato and Aristotle the good life could only be lived in a free city-state, like the little independent Greek cities which they knew ; but these had now fallen under the empire of Macedon, and the barrier between Greek and barbarian was giving way. The wars of Alexander's successors [, followed by the seemingly endless wars first between the Successors and Rome, and then between and among the Romans,] rendered all things insecure : exile, slavery, violent death were possibilities with which every man must lay his account.

~Rackham, Introduction to Cicero's de Finibus, xviii.

Bill Weintraub :

"exile, slavery, violent death were possibilities with which every man must lay his account"

Every Man :

Virgil, Varius, Cicero, Maecenas, Pollio, Sallust, Brutus, Cassius, Octavian, Agrippa, Antony -- and not least Horace and Horace's father -- all faced exile, slavery, violent death.

They all did.

Horace was indeed "too familiar with death and danger."

They all were, and they cannot be understood without taking that into account.

For example, Prof Rudd :

Though he was doubtless wary of Octavian (Augustus after 27 b.c.), Horace recognized that Augustus had brought peace and the hope of recovery. To most sections of the populace Augustus also brought greater freedom, namely the provincials, the equites, and the plebs. True, the power of the senate was broken beyond repair, but Horace may never have had much enthusiasm for the old oligarchic system [in which he would forever have been "son of a freedman father."].

Bill Weintraub :

It's reasonable to suggest that Horace would have initially been wary of Octavian.

He had, after all, fought against him at Philippi.

But over the ensuing years, and certainly once Horace had been accepted as a client by Maecenas, who, according to the Oxford Classical Dictionary, had been "among Octavian's earliest supporters -- he'd fought at Philippi -- [and] was Octavian's intimate and trusted friend and agent," Horace's attitude would have changed.

As Prof Bennett makes clear in his narrative of Horace's life :

After some two years at Athens Horace's studies were interrupted by political events, Caesar had been assassinated in March of 44 b.c., and in September of that year Brutus arrived in Athens, burning with the spirit of republicanism. Horace was easily induced to join his standard, and, though lacking previous military training or experience, received the important appointment of tribunus militum in Brutus' army. The battle of Philippi (November, 42 b.c.) sounded the death-knell of republican hopes and left Horace in bad case. His excellent father had died, and the scant patrimony which would have descended to the poet had been confiscated by Octavian in consequence of the son's support of Brutus and Cassius.Taking advantage of the general amnesty granted by Octavian, Horace returned to Rome in 41 b.c., and there secured a position as quaestor's clerk (scriba), devoting his intervals of leisure to composition in verse. He soon formed a warm friendship with Virgil, then just beginning his career as a poet, and with Vairius ; through their influence he was admitted (39 b.c.) to the friendship and intimacy of Maecenas, the confidential adviser of Octavian, and a generous patron of literature. About six years later (probably 33 b.c.) he received from Maecenas the Sabine Farm, situated some twenty-five miles to the northeast of Rome, in the valley of the Digentia, a small stream flowing into the Anio. This estate was not merely adequate for his support, enabling him to devote his entire energy to study and poetry, but was an unfailing source of happiness as well ; Horace never wearies of singing its praises.

Horace's friendship with Maecenas, together with his own admirable social qualities and poetic gifts, won him an easy entrance into the best Roman society. His Odes bear eloquent testimony to his friendship with nearly all the eminent Romans of his time. Among these were: Agrippa, Octavian's trusted general and later his son-in-law ; Messalla, the friend of Horace's Athenian student days, and later one of the foremost orators of the age ; Pollio, distinguished alike in the fields of letters, oratory, and arms. The poets Virgil and Varius have already been mentioned. Other literary friends were : Quintilius Varus, Valgius, Plotius, Aristius Fuscus, and the poet Tibullus.

With the Emperor, Horace's relations were intimate and cordial. Though the poet had fought with conviction under Brutus and Cassius at Philippi, yet he possessed too much sense and patriotism to be capable of ignoring the splendid promise of stability and good government held out by the new regime inaugurated by Augustus. In sincere and loyal devotion to his sovereign, he not merely accepted the new order, but lent the best efforts of his verse to glorifying and strengthening it.

He died November 27, 8 b.c., shortly before the completion of his fifty-seventh year, and but a few weeks after the death of his patron and friend Maecenas.

. . .

As a master of lyric form Horace is unexcelled among Roman poets. In content also many of his odes represent the highest order of poetry. His patriotism was genuine, his devotion to Augustus was profound, his faith in the moral law was deep and clear. Wherever he touches on these themes he speaks with conviction and sincerity.

"His faith in the moral law" -- courage, constancy, loyalty, piety -- "was deep and clear" :

The brave are born from the brave and good [fortis et bonus]. Their sires' valour [virtus] comes out in young bulls and horses ; ferocious eagles do not father timid doves.

But training [doctrina] develops innate powers, and the inculcation of what is right strengthens the heart [recte cultus pectora roborat].

When sound principles cease to be observed, even the wellborn are disgraced by sin.

~Odes IV.IV, The Feats of Drusus, translated by Rudd.

One would not be right [recte] to call happy [beatus] the man of many possessions ; the title of happy is more rightly claimed by the man who knows how to use with wisdom the gifts [muneribus] of the Gods, and to endure the rigours of poverty [that is, to live frugally], and who fears dishonour worse than death, not afraid to die for cherished friends or fatherland.

~Odes IV.IX, In Praise of Lollius, translated by Bennett.

[Horace is making conversation with his patron Maecenas :]

"Is the Thracian Chicken a match for Syrus?" [a]

Footnote from Prof Fairclough :[a] The reference is to some sporting event of the day. The men mentioned were gladiators, one being armed like a Thracian.

Bill Weintraub :

Yet when with his friends, says Horace, "we discuss matters which concern us more, and of which it is harmful to be in ignorance -- whether wealth or virtue [virtus] makes men happy, whether self-interest or uprightness [rectum] leads us to friendship, what is the nature of the good and what is its highest form [summum bonum]. [c]"

Footnote from Prof Fairclough :[c] Fundamental questions of ethical philosophy.

~Satires 2.6.44, translated by Fairclough. [ p 215 ]

Let the youth, toughened by the constraints of a soldier's life and hardened by active service, learn to bear with patience trying hardships! Let him, a horseman dreaded for his lance, harass the warlike Parthians and pass his life beneath the open sky amid stirring deeds! At sight of him from foeman's battlements may the consort of the warring tyrant and the ripe maiden sigh : "Ah, let not our royal lover, unpractised in the fray, rouse the lion fierce to touch, whom rage for blood hurries through the midst of carnage!"

'Tis sweet and fitting to die for fatherland [Dulce et Decorum est Pro Patria Mori]. Yet death hunts down also the runaway, nor spares the limbs and coward backs of faint-hearted youths.

True Manhood [virtus], that never knows ignoble defeat, shines with undimmed glory, nor takes up nor lays aside the axes [securis -- an axe, esp the headman's axe, thus the axe carried in the fasces -- symbols of authority and Roman supremacy] at the fickle mob's behest [1].

Footnotes:From Prof Rudd :

[1] It is not altogether fanciful to see these lines as an allusion to an attempt by the Princeps [Octavian] to introduce moral legislation in 28 b.c.

From Bill Weintraub :

[1] In 28 bc, Octavian, who became Augustus in 27 bc, put forward laws for the moral regeneration of the Roman people.

The proposed laws occasioned heavy opposition, and Octavian withdrew them.

But in 18 bc, when his power was far more secure, he put them forward again and they were enacted.

And Horace, as we can see, and not surprisingly given the way he'd been brought up by his father, strongly supported those laws and Augustus' persistence in bringing them to fruition.

True Manhood [virtus], opening Heaven wide for those deserving not to die, essays its course by a path denied to others, and spurns the vulgar crowd and the damp earth with its soaring wing.

There is also a sure reward for faithful silence [fides silentio]. I will forbid anyone who has divulged the sacred rites of mystic Ceres to abide beneath the same roof or to unmoor with me the fragile bark. When slighted, Jupiter often lumps the righteous together with the impious ; but rarely does Retribution, albeit of halting gait, fail to overtake the guilty.

~Odes III.II, Endurance, and Fidelity to One's Trust, translated by Bennett and Rudd.

Bill Weintraub :

Ode III.II illustrates the four "traditional values of courage, constancy, loyalty, and piety" cited by Prof Rudd : courage, which is Virtus ; constancy, which is Fortitudo ; and loyalty -- Fides ; and piety -- Pietas.

These values, traditionally Italian as well as Roman, were now, in no small part thanks to Cicero, receiving even more emphasis through the ascendancy of the relatively new religious philosophy of Stoicism.

And they were values shared by Augustus and Horace -- who both came from Italian towns.

"The new regime," says Rudd, "was keen to restore" these values.

And Horace was glad to help.

Because, clearly, those values were his own.

The man tenacious of his purpose in a righteous cause is not shaken from his firm resolve by the frenzy of his fellow citizens bidding what is wrong, not by the face of threatening tyrant, not by Auster, stormy master of the restless Adriatic, not by the mighty hand of thundering Jove. Were the vault of heaven to break and fall upon him, its ruins would smite him undismayed.

'Twas by such merits that Pollux [God of Boxers] and roving Hercules [God of Gladiators] strove and reached the starry citadels, reclining among whom Augustus shall sip nectar with ruddy lips. 'Twas for such merits, Father Bacchus, that thy tigers drew thee in well-earned triumph, wearing the yoke on untrained neck. 'Twas for such merits that Quirinus [Romulus] escaped Acheron [Death] on the steeds of Mars, what time Juno, among the Gods in council gathered, spake the welcome words . . .

~Odes III.III, Justice, and Steadfastness of Purpose, translated by Bennett.

Descend from heaven, Queen Calliope, and come, sing a lengthy song with the pipe or, if you prefer, with your clear voice alone, or with the strings and lyre of Phoebus. Do you hear, my friends? Or am I misled by a fond delusion? I seem to hear her and to be walking in a sacred grove, through which delightful streams and breezes wander. On pathless Vulture, [a mountain near Horace's hometown of Venusia] beyond the threshold of my nurse's cottage, when as a child I was worn out with play and sleep, the legendary wood pigeons covered me with fresh leaves. It was a marvel to all who live in the eyrie of lofty Acherontia and Bantia's glades and the rich plough land of low-lying Forentum how I slept with my body unharmed by bears and black vipers, how I was hidden under piles of sacred laurel and myrtle, thanks to the Gods a spirited child.

I am yours, Muses, yes, yours when borne aloft to the Sabine region, yours whether I prefer cool Praeneste or sloping Tibur or Baiae with its limpid air. Because I loved your springs and dances, I was not destroyed by the rout of our line at Philippi, nor by that accursed tree, [1] nor by Palinurus with his Sicilian waters. [2]

Footnotes:From Bill Weintraub :

[1] A tree on Horace's Sabine Farm almost fell on him, and in so doing would have killed him, but for the intervention of the God Faunus.

From Prof Rudd :

[2] Palinurus: a headland on the coast of Lucania. The incident in which Horace escaped drowning took place during Octavian's struggle against Pompey's son, Sextus in 36 b.c.

So long as you are with me, I shall gladly become a sailor and venture into the raging Bosphorus, or a traveller and brave the burning sands of Syria's shore. Immune from violence, I shall visit the Britons, who are hostile to foreigners, the Concanian who enjoys drinking horse's blood, the Geloni with their quivers, and the Scythian river.

You refresh our exalted Caesar within a Pierian grotto, as he seeks to bring his labours to an end, now that he has unobtrusively settled in the towns his cohorts weary with campaigning. [3] You in your kindness give him gentle advice, and are glad to have given it. We know how the impious Titans and their outlandish troops were eliminated by the hurtling thunderbolt of him who controls the torpid earth, the windy sea, and the ghosts in the realms of gloom, and who rules alone with impartial authority both the Gods and the hordes of men. [4]

Footnotes from Prof Rudd :[3] After the war against Antony and Cleopatra [31-30 bc].

[4] The mythical revolts against Jupiter (Zeus) are seen as a parallel to the battles of Actium and Alexandria.

~Odes III.IV, Poetic and Political Harmony, translated by Bennett and Rudd.

Though guiltless, you will continue to pay for the sins of your forefathers, Roman, until you repair the crumbling temples and shrines of the Gods [1], and the statues that are begrimed with black smoke.

Footnote from Prof Rudd :

[1] Augustus' building program, already under way.

'Tis by holding thyself the servant of the Gods that thou dost rule ; with them all things begin ; to them ascribe the outcome !

Outraged, they have visited unnumbered woes on sorrowing Hesperia. Already twice Monaeses and the band of Pacorus have crushed our ill-starred onslaughts, and now beam with joy to have added spoil from us to their paltry necklaces. Beset with civil strife, the City has narrowly escaped destruction at the hands of Dacian and of Aethiop, the one sore dreaded for his fleet, the other better with the flying arrow.

Teeming with sin, our times have sullied first the marriage-bed, our offspring, and our homes ; sprung from this source, disaster's stream has engulfed the folk and Fatherland. The maiden early takes delight in learning Grecian dances, and trains herself in coquetry even now, and plans unholy amours, with passion unrestrained. Soon midst her husband's revels she seeks younger paramours, nor stops to choose on whom she swiftly shall bestow illicit joys when lights are banished ; but openly, when bidden, and not without her husband's knowledge, she rises, be it some peddler summons her, or the captain of some Spanish ship, lavish purchaser of shame.

Not such the sires of whom were sprung the youth that dyed the sea with Punic blood, and struck down Pyrrhus and great Antiochus and Hannibal, the dire ; but a manly brood of peasant soldiers, taught to turn the clods with Sabine [Spartan] hoe, and at a strict mother's bidding to bring cut firewood, when the sun shifted the shadows of the mountain sides and lifted the yoke from weary steers, bringing the welcome time of rest with his departing car.

What do the ravages of time not injure ! Our parents' age, worse than our grandsires', has brought forth us less worthy and destined soon to yield an offspring still more wicked.

~Odes III.VI, Religion and Purity, translated by Bennett and Rudd.

Wretched the maids who may not give play to love nor drown their cares in sweet wine, or who lose heart, fearing the lash of an uncle's tongue. From thee, O Neobule, Cytherea's winged child [Cupid] snatches away thy woolbasket ; thy web, and thy devotion to Minerva, are stolen by the brilliant beauty of Hebrus from Lipara, as soon as he bathes his oiled shoulders in the waters of the Tiber, a rider better even than Bellerophon, never defeated for fault of fist or foot [1], clever too to spear the stags flying in startled herd over the open plain, and quick to meet the wild boar lurking in the thick-set copse.

Footnote from Bill Weintraub :[1] "never defeated for fault of fist or foot" = "neque pugno neque segni pede victus" = pugno victus = "the unconquered fist, conquering fist"

~Odes III.XII, Poor Neobule, translated by Bennett and Rudd.

Pugno Victus

Conquering Fist

As I've said, in a society which valued friends, Horace had an extraordinary talent for friendship.

Here are two examples :

QUINTVS HORATIVS FLACCVS

AKA

HORACE

TESTIMONIA Pompeius' return

My friend,[12] so often carried with me into moments of the utmost peril when Brutus was in charge of operations,[13] who has restored you to your father's Gods and the sky of Italy, to be a citizen once again?[14]Pompeius, dearest of my comrades, many's the time that in your company I have broken the long day's tedium with neat wine, my garlanded hair glistening with Syrian perfume. With you beside me I experienced Philippi and its headlong rout, leaving my little shield behind without much credit,[15] when valour [virtus] was broken and threatening warriors ignominiously bit the dust. I, however, was swiftly caught up by Mercury[16] in a thick cloud and carried trembling through the enemy's ranks, whereas you were sucked back into war by the current and borne away by the seething tide.

So then, pay to Jove the feast he deserves ; lay down your limbs, worn out as they are by long campaigning, beneath my bay tree, and give no quarter to the jars set aside for you. Fill up the polished cups with Massic that dulls the memory, pour scented oils from capacious shells. Whose job is it to come up right away with garlands of moist celery or myrtle? Who will be declared toastmaster by Venus' throw?[17] I shall revel with all the madness of a Thracian ; it is sheer delight to go wild, for I have got back my friend.

~Horace, Odes II.VII, Pompeius' Return, translated by Niall Rudd.

Footnotes :

12 Nothing else is known of this man.

13 Those that ended at Philippi in 42 b.c.

14 An allusion to Octavian, who sanctioned his return, perhaps in 30 b.c.

15 Possibly true, but the motif is conventional in Greek poetry.

16 Inventor of the lyre, hence patron of poets.

17 The highest throw with the dice.

QUINTVS HORATIVS FLACCVS

AKA

HORACE

TESTIMONIA Despair not, Maecenas ! One Star Links our Destinies

Why dost thou crush out my life by thy complaints?

'Tis the will neither of the Gods nor of myself that I should pass away before thee, Maecenas, the great glory and prop of my own existence.

Alas, if some untimely blow snatches thee, the half of my own life, away, why do I, the other half, still linger on, neither so dear as before nor surviving whole ? That fatal day shall bring the doom of both of us. No false oath have I taken ; both, both together, will we go, whene'er thou leadest the way, prepared as comrades to travel the final journey.

Me no fiery breath of Chimaera, nor hundred-handed Gyas, should he rise against me, shall ever tear from thee. Such is the will of mighty Justice and the Fates. Whether Libra or dread Scorpio or Capricornus, Lord of the Hesperian wave, dominates my horoscope as the more potent influence of my natal hour, the stars of us twain are wondrously linked together.

To thee the protecting power of Jove, outshining that of baleful Saturn, brought rescue, and stayed the wings of swift Fate that time the thronging people thrice broke into glad applause in the theatre. Me the trunk of a tree, descending on my head, had snatched away, had not Faunus, protector of poets, with his light hand warded off the stroke.

Remember then to offer the victims due and to build a votive shrine ! I will sacrifice a humble lamb.

~Horace, Odes, II.XVII, Despair not, Maecenas ! One Star Links our Destinies.

The translation is by CE Bennett, 1912.

And the applause at the theater was for Maecenas on his return to public life after a dangerous illness.

"No false oath have I taken ; both, both together, will we go, whene'er thou leadest the way, prepared as comrades to travel the final journey."

And, in fact, Maecenas died in late September 8 BC, and Horace followed just a couple months later.

The two Men were -- and perhaps still are -- buried near each other on the Esquiline Hill.

What was the true nature of the relationship between them ?

It's impossible to know.

But here's a hint from Prof Rudd :

Maecenas died at the end of September 8 b.c., and in his will he gave an instruction to Augustus: "Remember Horatius Flaccus as you remember me." As if recalling what he had said in II.XVII.10-12 ("both, both together, will we go, whene'er thou leadest the way, prepared as comrades to travel the final journey"), Horace followed on November 27th. They buried him near Maecenas on the Esquiline Hill.Maecenas' words to Augustus, Horace's to Maecenas, the decision to bury Maecenas and Horace near each other, are all powerful statements -- of Love and Affection -- from and for a great poet and his faithful friend.

Bacchus, the Liberator,

here depicted on a wall in Pompeii

Horace often speaks of wine as a bringer of joy

The Great Phallic God Priapus

Who punishes those who steal

the fruits of the earth -- with impotence.

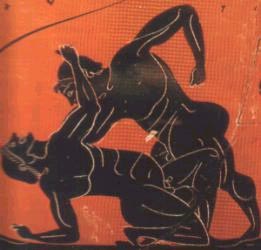

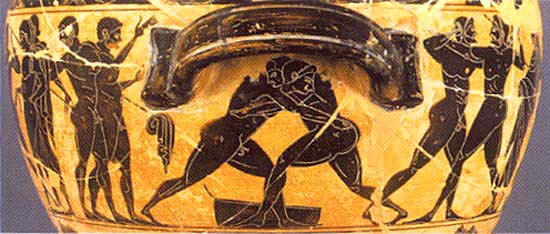

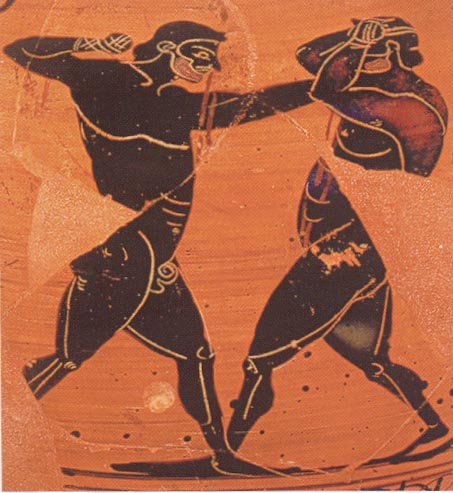

A Victorius Gladiator

Worships the God

Hercules

And here are images of a Thermopolium, a sort of fast-food restaurant, in Pompeii :

The brave are born from the brave and good. Their sires' valour comes out in young bulls and horses ; ferocious eagles do not father timid doves. But training develops innate powers, and the inculcation of what is right strengthens the heart.

Bill Weintraub :

This first passage echos and affirms what Aristotle says :

A Man's Valour -- his Virtus -- which is both Willingness and Ability -- is in part a heritage from his Father.

But Men need Training as well.

"training develops innate powers, and the inculcation of what is right strengthens the heart" Inculcation is the development of habits -- habits of Manliness.

Habits of Manliness strengthen the Heart -- the source of Valour.

While Training develops Ability.

Virtus -- Manliness -- is the Willingness and Ability to Fight.

When sound principles cease to be observed, even the wellborn are disgraced by sin.

What you, Rome, owe to Drusus and his brother Tiberius is attested by the river Metaurus, by the overthrow of Hasdrubal, and by that glorious day which, driving the dark clouds away from Latium, was the first to smile with heartening victory since the dreaded African Hannibal galloped through the towns of Italy like a fire through pine trees or the East Wind through Sicilian waves. After that the young men of Rome grew strong through struggles that were always successful ; and shrines wrecked by the impious depredations of the Carthaginians once more housed Gods that stood upright.

~Horace, Odes, IV.4, The Feats of Drusus, translated by Rudd.

The fickle public has changed its taste and is fired throughout with a scribbling craze ; sons and grave sires sup crowned with leaves and dictate their lines.[to an amanuensis] I myself, who declare that I write no verses, prove to be more of a liar than the Parthians : before sunrise I wake, and call for pen, paper, and writing-case. A man who knows nothing of a ship fears to handle one ; no one dares to give southernwood to the sick unless he has learnt its use ; doctors undertake a doctor's work ; carpenters handle carpenters' tools : but, skilled or unskilled, we scribble poetry, all alike.

And yet this craze, this mild madness, has its merits. How great these are, now consider. Seldom is the poet's heart set on gain : verses he loves ; this is his one passion. Money losses, runaway slaves, fires -- he laughs at all. To cheat partner or youthful ward he never plans. His food is pulse and coarse bread. Though a poor soldier, and slow in the field, he serves the State [utilis urbi], if you grant that even by small things are great ends helped.

The poet fashions the tender, lisping lips of childhood ; even then he turns the ear from unseemly words ; presently, too, he moulds the heart by kindly precepts, correcting roughness and envy and anger. He tells of noble deeds, equips the rising age with famous examples, and to the helpless and sick at heart brings comfort.

[ll. 132-3] Whence, in company with chaste boys, would the unwedded maid learn the suppliant hymn, had the Muse not given them a bard?

[ll. 134-7] Their chorus asks for aid and feels the presence of the Gods, calls for showers from heaven, winning favour with the prayer he has taught, averts disease, drives away dreaded dangers, gains peace and a season rich in fruits. Song wins grace with the Gods above, song wins it with the Gods below.[a]

Footnote from Prof Fairclough :

[a] In ll. 132-133, Horace is thinking chiefly of the chorus of chaste boys and maiden girls who sang the Carmen Saeculare in 17 b.c. ; in ll. 134-137, he sets forth the function of the chorus, especially in association with religious ceremonies.

~Horace, Epistles II, Book II, To Augustus

"Chaste Boys."

Only Chaste Boys and Maidens were allowed to sing the Carmen Saeculare, the Hymn for a New Age, commissioned by Augustus, written by Horace, and performed in 17 BC at ceremonies celebrating the tenth year of Augustus' rule.

The Romans were very pious, and it was, says Prof Rudd, "the traditional values of courage, constancy, loyalty, and piety which the new regime was keen to restore."

And Horace, who shared those values, whose "faith in the moral law was deep and clear," says Prof Bennett, was glad to oblige.

That faith and those values were, after all, the Faith and Values Horace had learned from his Father, the Best of Fathers, who'd Protected him and kept him Chaste.

And who'd taught his son that Chastity is the First Grace of Manhood.

Bill Weintraub

June 9, 2021

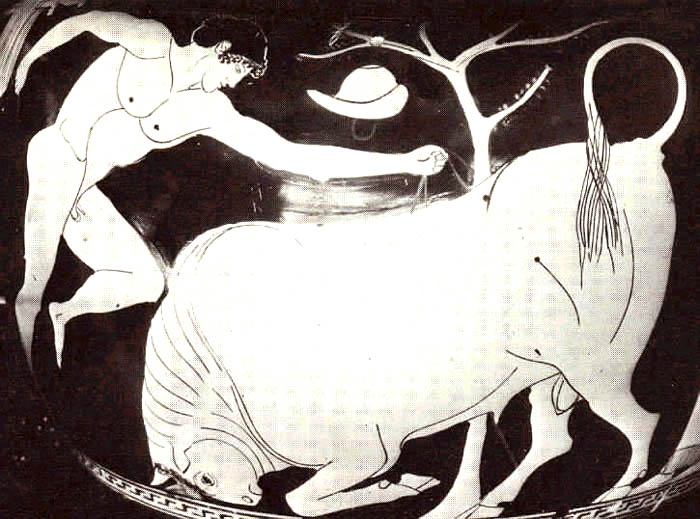

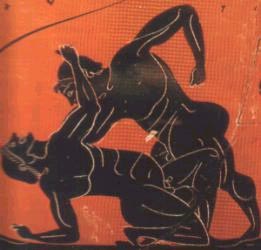

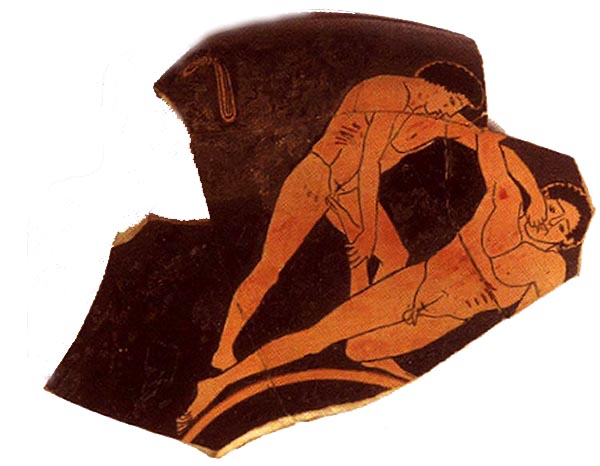

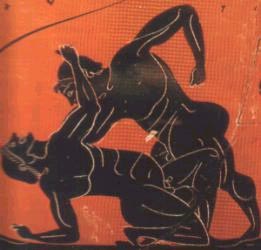

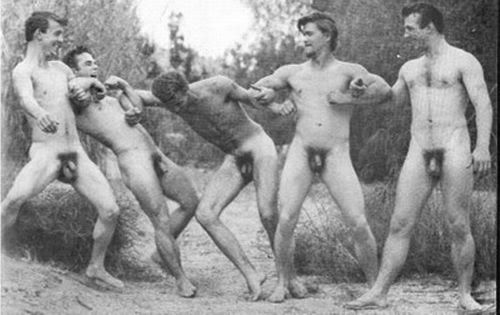

Gladiators after the Fight

The Calm after the Storm